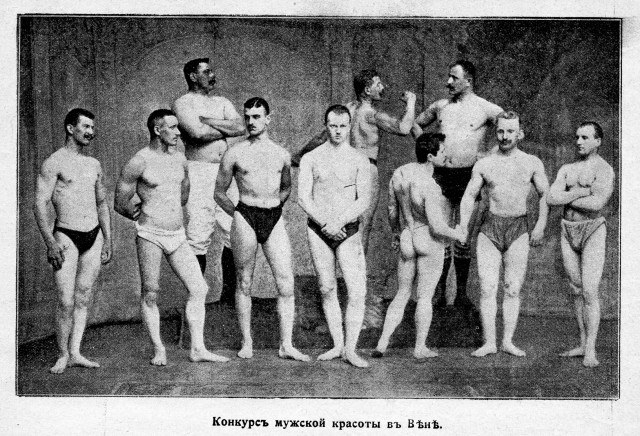

Modern culture subjects men’s as well as women’s appearance to analysis, control and careful scrutiny. While the “making” of a woman’s body is out there for everyone to see (TV, newspapers, magazines), the construction of a man’s body is largely restricted to what one might call “men’s ghettos of beauty and strength”: gyms and sports clubs.

Professional sport creates and maintains a cult of competition: what matters is not participating but winning. For instance, champions become national heroes and often media celebrities. To a large extent, it is precisely this level of publicity that is grasped by the youth: its visual images become a magnet attracting young people into the world of amateur sports.

Here, the body is not considered important as such, but rather in terms of the values that stand “behind it”: confidence, beauty, power. When it meets the culture of spectacle, masculinity departs from the general line of physical strength and domination: a connection emerges between professional sports, media popularity and practiсes of “care and wellness”.

Taking care of one’s appearance is rather at odds with the notions of masculinity. The basic normative features of any male culture are high competitiveness, aggression, ambition, the love of novelty and risk, “coolness”. It is composed of practices that underpin the power of men over women in general and of certain men over other men.

However, in the modern world those principles clash with new images of men where it’s not the aggressive physical force that comes to the fore but the ability to “solve problems elegantly”. Components such as professionalism, care of one’s health, attractiveness gain in importance. Nevertheless, the new normative characteristics do not replace the old ones but layer over them, and it is that mix that becomes the foundation of young men’s identities.

“My initial goal was to buff up so that I would be able to wear sleeveless shirts. You know, like models or former athletes. I had a very mediocre body. Nothing special: regular arms and legs, like sticks”.

(from an interview at a Minsk gym)

Being unhappy with one’s body is a form of denial, nonacceptance, disgust. And all disgust creates and destroys the subject at the same time. At this point we face the traumatic nature of our own being and, if we walk this path further, the horror of the Real. The lack that needs to be hidden, to be covered under superficial features.

The process of constructing oneself may be considered as a quote, a performance. In this sense, masculinity constitutes a constant repetition of images that have already been revealed. It is a sort of carnival costume that serves the double purpose of, firstly, hiding one’s “true” face, the existence whereof is doubtful, and secondly, clearly and unambiguously representing the character, playing the role. While for adult men, their actual status, money, professional success constitute their resources, for the younger ones they are rather made up of their physical and psychological characteristics.

“I came to the gym to feel freer, more confident. I mean, I cannot say that I wasn’t confident, no, but something was missing, — says a young man. — So I decided to take care of my body”.

(from an interview at a Minsk gym)

The Self and the Others

“We aren’t at all like planets, that’s something we can have a sense of whenever we want, but that doesn’t prevent us from forgetting it.” Those words by philosopher Jacques Lacan emphasise the specifics of the relationship between the external world and the human Ego.

The Other is someone who is different from me, the “non-Ego”. The Big Other is a category of the symbolic order, he is better and more dangerous than the Ego. He threatens my wholeness and value. The Other is all around the Ego: apart from the outward image we are faced with the internal law: the psychoanalytical Name of the Father that is the unattainable role model that threatens with a punishment for not meeting its standard. In this sense other men’s gaze, their appraisal matters most:

“At first, I felt awkward, even ashamed of myself, I mean, that I had no muscles at all. But on the other hand, I wanted to prove to everyone that I could be a beefcake too. It was important to me that people notice it, the way my body changed”.

(from an interview at a Minsk gym)

This is how one of the interviewed describes his initial motivation to go to the gym:

“I wanted to change in order to look better, so that people would notice me”.

When asked whether those people’s sex mattered to him, he answers:

“No, there’s no difference at all. In fact, a man looking probably matters even more. When you can look and realize you are stronger than him”.

Another young man says:

“I’m afraid I’ll never be able to quit the gym. I’m afraid of stopping being a jock, of losing my shape”.

In the interviews, the young men who go to the gym constantly speak of themselves in comparison, referring in one way or another to real or imagined visual images. When they work out at the machines, the men look at themselves as The Other: they may be satisfied with their reflection in the mirror or not, but in any case this image is different from their own real body. It returns the Gaze, under the heaviness whereof the subject becomes aware of his own imperfection, insufficiency. The situation described is the communication between the Ego and the “ideal image”, while the reflecting surface is but a projection of the Ego’s ideas and fantasies about the “real” body.

Another important element of these sport practices is their uniting effect. This is what one of the interviewees says about the atmosphere in the gym:

“All in all, everyone shows off before each other, it seems like people talk, discuss their successes, but they always look sideways to see how much you’re lifting, if it’s more or less than them”.

Despite the cultivation of male brotherhood, the sports club community only looks homogeneous at first sight: in fact, there are many differences inside that serve as a basis for a hierarchy. The relationships between men in this community are symbolic power games, where the highest place is taken by the most experienced, the strongest, and the most attractive. That is why, on the one hand, there is an atmosphere of brotherhood at the gym, which, on the other, implies automatically a permanent fight over leadership.

The Male and Female Bodies in Sport

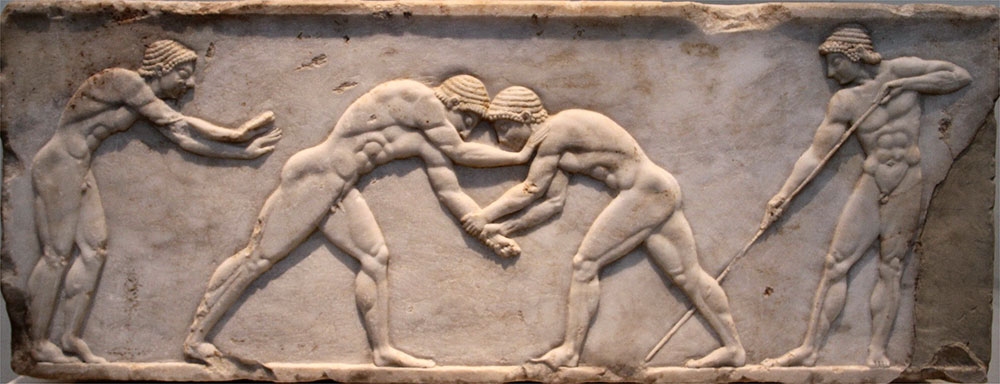

Even at the most obvious level, the topic of corporeality confronts us with the issue of difference and differentiation. In sports practices, an extreme polarisation of the male and the female manifests itself. The phallocentric culture is based on the exaggerated role of the masculine and (in)direct devaluation of the feminine. Its characteristic feature are binary oppositions: the masculine is seen as active and effective, and the female is represented as absent.

In fact, the only gender represented in culture is the male, while the female is pushed to the periphery. This causes a value imbalance, which means that everything related to the feminine is seen as less significant and less important. This observation is important in the context that the interviews were not held in a typical gym, set up for a unisex culture of a “healthy lifestyle”, but in a sports club. The latter rather represents a somewhat modernised Soviet-type gym.

This is why the gender imbalance is critical: as a rule, there are one to three women at the gym against ten to thirteen men. “Male brotherhood” and the cult of masculinity are quite apparent in this setting. For example, this is a telling dialogue during a training session:

— Chicks shouldn’t come inside the gym anyway, so they don’t distract us. Least of all today, as it’s Sunday. They should be everywhere else but not here.

— No, come on, it’s a free energy boost. I don’t mind.

The presence of a woman at the gym is seen in the context of being for men, i.e. beyond the idea of her own training. At the gym, a group of men of different ages and social statuses emerges that is united around a common idea. However, this community is only possible provided that its collective identity is constructed with regard to a strict disposition of the “masculine/feminine”, where the former is active, strong and big, and the latter is passive, weak and fragile. In general, sport as a public spectacle shapes and centers the ideology of male supremacy over women, and rich supremacy over the poor. That is how the “female” is rejected as the other: the female body is empty, good-for-nothing, in the terms of the gym it is described as imperfect, inadequate, it can only imitate, chasing the “force” and “shape”, but never achieving them.

It also seems telling that when women turn to their bodies, it mostly boils down to its reduction, to bringing it to naught, while with the male body it is the contrary: it makes itself grow, gain mass and power, becomes bigger in all senses.

At the same time, a certain mutation can be observed, when the gym, i.e. the the zone of hegemonic masculinity, turns into a space for admiration of one’s own mirror reflection. This is how, against the backdrop of physical power, it is still the the notions of beauty and visual pleasure that come to the fore. The interviewees speak of their own bodies in the following way:

“Before, I didn’t like looking at myself, now it’s the contrary. Others notice it too that I’ve changed to the better, they pay me compliments”.

Among other things, the young men interviewed speak of their aversion to the “muscleheads” who “overdo it”, because it looks, according to the speakers, unnatural and outright horrifying. To them, the ideal of a man’s body matches the image from fashion magazines and movies: it is “muscular and handsome”. Therefore, the decisive role is not played here by the drive towards hegemonic masculinity, but rather by the passion for the images derived from consumerist culture.

“Yes, I’ve cut the fat thanks to my diet, but I lost almost all I’d gained. The results dropped immediately, I got depressed, I didn’t want to exercise at all, I didn’t want anything. But I had to lose weight anyway, because otherwise there’s no point in going to the gym: nobody will see your six-pack under all the fat”.

Strength training practices of constructing one’s body fill in two “gaps” at once: first, this is a potential opportunity to showcase physical strength (“I would never get into a fight before, but now I would because I have become stronger”), and second, the conformity to the media image of beauty, which is associated with success. In other words, this is a new type of masculinity based on a combination of brutal and metrosexual features.

Although all the interview participants have repeated that the leading motive behind their work-out efforts was a chase after “freedom”, instead they have created a disciplinary space of rigorous practice around themselves. On the one hand, the gym is an attempt to change oneself through adherence to archaic images that were powerful in the past. In this sense, appealing to a group identity through drawing on the images of dominant masculinity is realising the need for a foothold in a world where patriarchal thinking is strong but still questioned. On the other hand, however, is is an attempt to conform to the modern metrosexual images as seen in the media.

In any case, the initial idea of “care” turns into a strict disciplinary framework where we fall hostages to our own idea of self as the Other who is better, stronger and more attractive than ourselves. Our own body is literally dismembered into separate parts, muscle groups, and subjugated to the standards of “beauty” and “strength”.