The reason for this article was the tragedy that happened to Mikhail Pishchevsky in May 2014.

Warning: The article contains instances of hate speech.

People often believe that silence over hate crimes is natural for societies that stand on holistic principles, i.e. on the premise that the whole always matters more than the particular. We rarely notice that the destructive influence of hate crimes falls first of all on the whole, i.e. the social system in its entirety. It would be naive to believe that incidents like that only threaten a certain community or a particular social group that is discriminated against and whose interests are seen as isolated. Paying no attention to the oppressed groups’ problems, pushing them to the periphery of the information space are always symptoms of a simulated positive social dynamic. The visual lack of discrimination-related problems means, in fact, that the information flow is censored in order to create a picture of “social wellbeing”.

©Daria Danilovich

The tendency to depict an incident as the victim’s isolated problem and to omit the hate motives when discussing aggressive behaviour has become common in the Belarusian public’s reaction to media reports. In this case we are speaking of multiple comments to information published on media websites and social networks. We are alarmed at the large number of commenters who express perplexity as to why the victim’s sexual orientation should be brought up at all in this context.

Three reaction types could be distinguished out of the totality of the comments: “don’t stick your head out and no one will touch you”, “what difference does it make that the victim was gay, I also got beaten, so what?” and “of course, I am against gays, but I don’t approve of the offender”:

“Had he lived a peaceful life and stayed at home, everything would have been normal. But no, he needed to have fun at gay parties, his own guys and girls”.

“… I think the root of the problem is that agiotage is being built up around people of non-traditional sexual orientation. Had there not been so much advertising of this in the media, there wouldn’t have been such hate on the part of the public…”

“I’ve long been saying that gay parties should be held in the woods. They haven’t listened and now there is this tragedy on their heads” etc.

Comments like that are dangerous primarily because they resort to victim blaming and shift the emphasis from violence by making it one particular person’s problem. They twist the cause and the effect in the crime in question by assuming that the victim had “provoked” violence towards himself merely by existing outside his personal space.

It is important for us to point out that such rhetoric is very dangerous. Not only does it fail to protect the victim from violence (Mikhail had lived in the closet and was attacked on his way back from a private party), but further than that, such crimes are in fact a direct consequence of the “closet policy” that is being imposed on the LGBTQ community. Besides, by relieving the aggressor of responsibility, society sanctions violence against a group that is discriminated against.

Staying in the closet is a significant factor contributing to increasing gender-based violence and discrimination in society. As with domestic violence, which is another type of gender-based violence, keeping silent leaves the abuse victim in isolation without the possibility to reach out for help or even to get support from family or friends. When the problem of violence against LGBTQ people is denied or tabooed in public conscience, it is harder for the public to recognise the motives behind it. This means that the victim will probably encounter denial, which increases psychological pressure and makes it more difficult to ask for help. For instance, Mikhail’s family was so scared of public pressure that they didn’t disclose the details of the crime for several months. As a result, the trial went down in total media silence and escaped not only public outrage, but also timely attention from human rights lawyers.

The second extremely common type of comments may be summarised as “What difference does it make?” As if copied one after another, the highlight the criminal intention universality by equating minor street assaults to homophobic attacks.

“… I’m probably too narrow minded to accept intolerance to sexual orientation as an aggravation. If I’m beaten up by someone drunk, can I consider myself assaulted based on intolerance toward IT professionals in Belarus?”

“… Don’t victimise homosexualists in our country. This is an isolated incident that can be contrasted with tens of thousands of assaults on heterosexual victims. It’s not a matter of sexual orientation, it’s just that there are quite a few drunk idiots in our streets at night who are ready to get violent without any particular reason…”

“There are hundreds of tragedies like this. It is absolutely wrong to say it happened because the victim was of irregular sexual orientation. Had he not been gay, the thugs would have found a different reason: because he had no cigarettes to share, because he looked at them the wrong way etc. That’s why we should focus on what happened, how to help and how to keep others safe in situations like this, but not on the fact that the victim happened to be gay…”

Comments like this were made despite the obvious nature of the hate-based motive of the crime that is clearly indicated in the article. However, in such comments it is not taken into account at all or gets downplayed to the minimum.

Why Are Homophobic Hate Crimes More Than Misdemeanour?

The danger with hate crimes is that by equating them to regular offenses, we erase the difference between horizontal civic interactions and the vertical relationship between an individual and social institutions. The social contract theory presumes that individuals alienate a number of liberties from themselves in exchange for an incontestable set of rights which the state stands to guarantee. This criterion for effective cooperation between the state machinery and civil society, developed by theoreticians of enlightened humanism back in the 17th century, lies in the foundation of today’s legal documents in democratic countries.

When prejudice and hate become motives for a crime, it is not only (and not so much) the matter of moral or physical harm suffered by a particular person. In this case the victim serves as a symbolic representative of a social group, and prejudice against that group is considered a ground for violating inalienable human rights.

Hate crimes are more than isolated instances of violence because they challenge the ideas of all citizens’ inherent equality and rule of law that are fundamental to our culture. The perpetrator doesn’t act against a specific person, group or community, they infringe on the authority of the state and law that guarantees personal liberties. When law institutions hush up or ignore the motive of hate, this indicates a problem with the state itself rather than within a particular local community. If a hate crime can only become visible as an isolated incident of aggression, we find ourselves in George Orwell’s Animal Farm: the declared equality of the parties to the social contract turns in practice to be a hierarchical oppression system, but nobody can talk about it because there is no precedent within the legal framework.

© Daria Danilovich

What are the consequences of the “closet policy”? First of all, it is the “invisibility” of this type of crimes, which in turn leads to perpetrators’ impunity and increasing risks that similar crimes will happen again. As a result, it is impossible to estimate the scale of violence against LGBTQ people in Belarus: due to the extreme homophobia, the victims rarely go to the militia, while those cases that do make it to trial are not, as we can see, treated as hate crimes. As of today there hasn’t been a single precedent in Belarus that the court would consider homophobia as an aggravation.

Recognising Hate Crimes Is the First Step Towards Fighting Them

The 2003 OSCE report recommendations clearly indicate that it is precisely recognition and condemnation of hate-based crimes at the state level that are an adequate response to criminal entities in the modern world and a way to strengthen justice and the rule of law. As global practice shows, in countries with anti-discriminatory legislation and effective data collection systems for hate crimes, the numbers of registered hate crimes are significantly higher than in those where this information is not tracked or is intentionally buried.

Let us consider the example of the 2008 OSCE countries statistics. The United Kingdom, which has a population of over 60 million according to the 2011 census, had 4.300 hate crimes against LGBT people registered in 2008. Sweden (population over 9 million as of 2011) reported 1.055 such cases. In Poland where the population is over 38 million according to the 2013 census, only 50 hate crimes against LGBT people were documented as part of a public campaign against homophobia. This difference does not indicate more pronounced xenophobia in the countries where the numbers are higher, but rather proves that in some countries shocking, cases of intolerance are buried under layers of social mimicry and legal formalism. But the damage from hate crimes for individuals as well as for the social system in general does not only vanish but rather increases due to silencing.

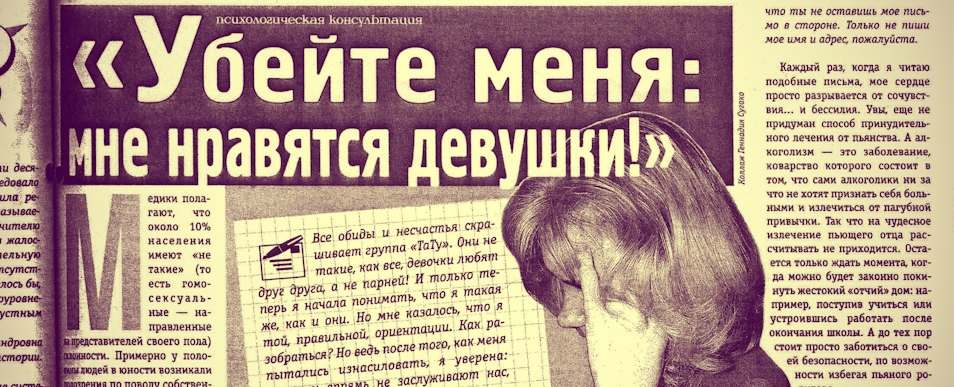

In Belarus where homophobic rhetoric is manifest at all levels of public relations: from interpersonal ones to public political statements, many believe that the closet policy will ensure security for all marginalised groups. It is no secret that the very idea of hate crimes is often associated with visibility, the visual side of being different. For instance, the athors of a 2012 report on monitoring xenophobia and extremism in Ukraine literally cite physical differentiation between “us” and “them” as a fundamental characteristic of xenophobic aggression: “Street racist attacks against the representatives of “visually distinguishable” minorities who are unambiguously identified in the crowd as “foreigners”, have repeatedly caused deaths”.

Mass media often appeal to the abstract concept of “society’s readiness” to recognise difference as a natural part of the social reality. They also often cite the population’s lack of education or use a rich pallet of victim blaming rhetorics in order to reassign the responsibility for violence to the victims themselves. But just as in the case of discursive exclusion of disabled people, pushing the LGBTQ community into the field of “invisibility” (from verbal aggression as a response to specific people’s personal politics of being out, to ways of covering LGBTQ-related topics in the media) doesn’t solve the problem of homophobia in society. Violence doesn’t go away but only transforms into socially acceptable manifestations of aggression and gets a loophole into the field of legality.