Does the place where you live influence the level of privacy in your life? Does living in the capital provide greater freedom in revealing your sexuality and gender identity? The stories of LGBTQIAP people born in small towns are an attempt to comprehend the connection between location and discrimination.

Polina, Orsha

I live in Orsha but study in Minsk (at the I.O. Akhremchik School of Arts). I’ve been studying here for only a year but I’ve immediately noticed the difference between Orsha and Minsk. In Minsk, there’se more possibilities. Here you can go to various lectures, workshops, educate yourself. But in Orsha there is nowhere to go but school. The people are very different too. For example, if you dye your hair in a bright colour in Orsha, everyone will look at you as if you were an alien, and in Minsk no one cares. Maybe it’s just my perception.

As to events back there, I honestly can’t remember anything. Maybe it’s because nothing ever happened. But I do remember people. My friends from Orsha always support me and try to understand me whatever happens. I’m very grateful to a friend of mine who was my team leader in a camp three year ago. She’s changed a lot in my life. She has always supported me, always said she accepted me the way I was. It was comforting to know that there was someone who didn’t care what society thought.

A couple years back only a few people knew about my orientation. Now I don’t hide it anymore, and almost all of my friends know I like girls.

In a small town there’s always the feeling that everyone knows everything about everyone else. Sometimes, when I talk to people I know, I notice that 70% of the information I receive from them is stories about who is dating whom and who has messaged whom on ask.fm. It’s depressing and often you just want to run away from the constant talk about people and their private lives.

With meeting people and dating, it’s really bad in Orsha. It seems to me there’s almost no unity because no one knows others. You simply don’t run across people other than glimpsing someone accidentally in the street. I know around a dozen LGBTQIAP people in Orsha but I just know they exist, that’s all. People meet kind of by chance. They write to each other on VKontakte or Instagram, or get introduced through mutual friends.

Three years ago there was a dating group, but no one runs it anymore so it’s empty. Also, two years ago people would gather in a group of ten or twelve at the stage in the town centre and hang out there. Now all of them have moved to different places.

Nasta, Vileyka

I associate Vileyka with my childhood and my teen years. It’s the town of my memories. I rarely go there now and when I do I barely leave my parents’ house. I have a very vague idea of what life in Vileyka is like today.

It’s a small town. The population is about thirty thousand. I used to live more or less at the heart of the town. There was a factory where they made Zenit cameras. Nearly the whole town worked at the factory. Our house was near it and a huge crowd used to pass by my windows during the lunch break, almost all Vileyka’s inhabitant.

Strong connections between people had an impact on me. It was hard to understand yourself and do what you wanted to do if it didn’t meet the expectations of those around. Because the community was very tight and you were part of it. Subconsciously you aspired to live up to their expectations.

If I think about sexuality and gender identity, then of course I was concerned about those issues back then. I don’t know if it had to do with living in a small town. I was very lonely, I had no support at all. But would it have been different had I lived in a big city? It was a time when at first there was no Internet at all. Later, as I went to high school, the Internet was there but I didn’t know anyone with access. Also, it was a very vulnerable age. When you’re a teenager, it’s often difficult to find support and understanding among grown-ups and your peers too. I think it was my age and lack of access to information that had the most impact on me and my morale.

When I lived in Vileyka I was a private person. I mean, nobody knew about me. I would only write in my diary and it was my only company.

I knew no one of Vileyka ’s LGBTQ community. Even now, after all these years, I can’t think of any one of the people I knew who might not have been heterosexual or сisgender. “I am the only one like that, there’s no one else like me,” I literally used to have these thoughts for a while.

I’ve never thought of myself as of a woman. Because on the one hand, that was my way to protect myself from patriarchy: I didn’t accept all those roles and labels and I could say to myself at one moment: “it’s fine, I’m not a woman anyway”. That’s why my non-binary identity played a positive role for me. It was easier to fight stereotypes that way, although sometimes I noticed that other people would want to squeeze me into the patriarchal woman image. I’ve always found it very weird.

Throughout my whole childhood I’ve been told I had to get married. That was the age when I didn’t understand what it meant to get married to begin with. But that sort of applied to everything. “You’re lazy, no one will marry you”, “you don’t study well, no one will marry you”. So I got that it was something bad. But I didn’t know what it was exactly.

Sometimes I would fall in love with girls in Vileyka. At high school I was in love with my classmate. I suffered a lot from not being able to tell her although I really wanted to. What would be the next step (after I told her), I couldn't even imagine, because that first step was impossible. I thought she’d treat me badly. We were friends and I could lose even that connection to her. It was better to stay friends than to lose everything. I didn’t want her to think I’d lied or pretended to be someone I wasn’t.

I felt as if it were some kind of disease inside me that would automatically spread on to her too if I told her about my feelings and she’d have to think what to do with it. I didn’t think she’d tell anyone and I’d be bullied. I only cared about her reaction.

Later, after I’d moved to Minsk, I talked to my classmates. We had a small class, we studied together from the first to the last year, no one’d swapped classes, we had were all close friends. I was afraid of ruining that. But after I went university I decided to talk to my closest girlfriends. And to the girl I was in love with. It was very important for me to find closure. Because I’d been thinking for quite a while she might’ve felt something too and maybe I wasn’t making the right call.

When you live in a small town, you always know at some point you’ll move to Minsk. When it’s time to go to university, that’s where you go. At least it was like that for me. It’s greater opportunities on the one hand, and normativity on the other. Because I didn’t have a choice, I didn’t think of what I really wanted (to go to Minsk, or a different city, or to stay in Vileyka). It was just a pattern which everyone around you would stick to. I didn’t have a single thought about whether it could be different.

I didn’t think of Minsk as liberation or salvation. It was hard for me to leave Vileyka, I missed my parents, and the city was new to me. Everything was strange and nothing attracted me there. In short, I didn’t think of Minsk as a city of opportunities. But apparently it has liberated me anyway, to an extent. I started making certain steps — at first I’d look for individual people, then for communities. I’d meet people in chatrooms, on dating websites, started going to parties.

My first coming out was when I was studying here in Minsk. At first I spoke to my friend. Then I came out to my Internet pen pal. It’s hard for me to comprehend what part the city had played in it. What mattered was rather the fact that I was trying to live my own private life, far from parents, regardless of others’ expectations for me. I started looking for what I liked, what I wanted. It would’ve been much harder to become conscious of myself had I stayed with my parents. The fact that there were meeting places in Minsk it didn’t mean you’d find what you were looking for. But at least there was the opportunity simply to see people.

There was also this newspaper called The Awkward Age which you could subscribe to everywhere. I also tried to speak to people on its pages. They started publishing letters from teenagers concerned about their sexuality. I remember letters like “I’m a lesbian, there’s something wrong with me, I hate myself, I need to do something about it, please help”. And psychologists would answer: “Oh, better not to tell anyone about it because you can never know how people will react”. On the one hand, that was their way of caring for the person but it was such weird advice. I remember how angry I was. I wrote them a letter. It was quite ardent, as in: “How can you give advice like that? You don’t understand how lonely people feel, how much they long for having someone, anyone to talk to. Do you realise that when you publish such advice, you take away the person’s opportunity to find understanding?” They didn’t answer me, nor did they publish the letter.

I didn’t know anything about LGBTQ people’s existence in Vileyka, I still don’t. But I’d probably like to go back to Vileyka and talk about that time with someone, to understand that it wasn’t so one-sided as I used to think.

It’s hard for me to go back to Vileyka. When I leave the house there I think: “I only hope I don’t run into anyone”. What would I tell them if they start asking? Will I be able to tell them that we have our own project on gender and sexuality? What words would I even use to tell them about it? Even my appearance has changed a lot. When I studied in Vileyka, I had long hair and wear dresses. That’s one of the reasons why it’s hard for me to speak about that time: I realise how much violence against myself there was.

I don’t go to school reunions, although I might at some point. Because in Vileyka, really good things happened to me too, and it’s an important part of my life. I just don’t know how to make it all agree within myself. It’s as if there were two Nastas: the one from the past and the one of the present.

When I imagine I do come to a reunion and I’m standing on the school stage — with a tattoo, short hair, unshaved legs, I understand that as I was growing up I’d have liked to see other representations than wome who look like women and men who look like men. There are different people and you are not in any sort of cage—I’d like for the current schoolchildren to hear it once they see me on that stage. That’s something I would have wanted to hear myself in my time.

Arciom, Babruysk

At the moment I consider myself gay. I’m saying “at the moment” because I used to like girls up until I was about fourteen. I live in Babruysk, it’s a town in the Mahilyow region. Many people know about it, it’s a famous Jewish town. It is the country’s largest city after the regional centres. There are a lot of people here, it’s not a village or something. Therefore it’s easier for LGBTQ people here than anywhere else in Belarus (apart from Minsk and the regional centres, of course). There is an LGBTQ community. You can talk to someone, feel you’re not alone.

In Babruysk I was very limited in terms of educational and cultural opportunities. Truth be told, that was why I wanted to go study in Minsk. In my home town there are no festivals, events, lectures like there are in Minsk. My self-realisation was limited. Everything that did influence my worldview in Babruysk had to do with people. They were people from various areas of my life: school, clubs, people I met right in the street. They gave me the passion for music, recommended good books that opened certain cultural phenomena to me (postmodernism, for example), spoke with me on different topics that I was concerned about. But unfortunately, they were still few.

I learned about Babruysk ’s LGBTQ community from people I knew. I simply made friends with a girl and later we learnt about each other’s sexual orientation, so she put me in touch with the town’s LGBTQ community. People find others like them and introduce them into the community through friends and acquaintances. But one must realise that it’s impossible to reach out to everyone like that.

At first, my friends didn’t know about my orientation, somehow I didn’t think of telling them. I just talked to them. But then I started to realise that I didn’t want to hide it forever because I had nothing to be ashamed of. First I told a classmate. She reacted very well and told me it wouldn’t change me in her eyes and I would remain her good friend just like before. Then I started expanding the circle of those who knew. If we speak about today, everyone who I have contacts to in Babruysk knows.

Of course, there were different conversations. People would ask me what the differences were or about the peculiarities of LGBTQ people. Everyone was curious: this is a living breathing person, but he is not like you. It is always interesting to hear a different view on life.

There were those who didn’t like it, too. Some stopped talking to me pointedly, made faces. That wasn’t pleasant, of course.

With Babruysk ’s LGBTQ crowd we’d simply go to walks, joke around and so on, what companies of friends normally do. There were only two or three guys, and the rest were girls. They were braver, they could kiss in a crowd and walk around holding hands. The guys didn’t even speak about being gay, let alone anything more. There were no leaders, everyone was equal. There were no rules or taboos either.

When we walked around the town, almost no one would pay attention to us. Well, some guys would catcall us sometimes. The locals only didn’t like it when we would hang out in someone’s yard. They’d shame us and say “children can see you” and “there’s a church near here, have you got no shame?”

I didn’t witness any fights. But a few times, when the butches were alone, someone would start fighting them. Well, honestly, the attackers were out of luck. Some of the girls they were trying to fight practised boxing, others karate, so they beat those guys good.

I had relationships in Babruysk. But only twice. Because there were too few people, it’s true. I was asked out more than this, but I said no. I realised: the fact that both of you are gay doesn’t necessarily mean you’ll date. We might differ in views or interests.

In Minsk there is a lot of events. Poetry readings, various art exhibitions, cheap concerts with all sorts of bands, LGBTQ events.

I have found many friends. And they are all different. Most are really good to me. That makes me happy.

Ryhor, Klimavichy

Klimavichy, 15 thousand inhabitants. Three schools, one preparatory school, an agricultural college and a vocational school. The famous spirits plant is one of the major employers. The central park is where young people go on a weekend night. Some go there to talk, sing songs and breathe the fresh air. Others just to take a walk along the few windy paths, see their friends, show off their new jeans and return home.

It’s a town where news spread in a blink of an eye.

When I think about the town and my sexuality, I can say that it was a restriction for me. For some reason I knew that I couldn’t date a guy from my town because that would entail having to play hide-and-seek with those who go to the preparatory school with me and those who I run into at the store, near my house or at events in town. Now I understand that this would have been a game played with myself because I didn’t know myself that well and wasn't ready to live to the fullest. But in any case, I would have never been able to be romantically involved with someone in my home town.

As a child I was forgiven for wearing mom’s shoes to the neighbour’s. Later on they called me a womaniser because my friends were mostly girls. But in the fifth or sixth grade, you’ll be called a fag even for having a pink pen.

A class in basic safety with a PE teacher. The boys are talking about a strange man in weird shoes. Everyone agrees that he is a “fag”, they smile together and feel glad about having found a solution: people like him should be beaten up. All that influences how out you can be, of course.

I would meet people from other towns, see them here and in other places. The Internet improves the environment, broadens it and helps fill socialisation gaps.

In tenth grade I made the final decision: Minsk would be the city of my student years. Around the same time I decided to tell my mother more about my life after I’d moved to Minsk. I think the distance played an important part here. But also the hope that life would be much easier there.

However, I didn’t come out after I moved. Naturally, Minsk with its safe spaces for various kinds of activities makes a lot of things easier. What you can learn in those places helps you live in full outside them. That is why Minsk provides certain opportunities to be yourself, however artificial this may sound in the context of the lies coming from multiple public service announcements.

Every country has its centre/centres where people move to in an incessant flow in the hope of finding professional opportunities or making new connections, in search for cultural development or spontaneous fun; they go where their dreams might come true.

In Belarus the centre is especially important. The capital is so enticing because the lack of activities is so prominent in other Belarusian towns. All the roads come to Minsk, the city of the sun and socialist realism in architecture. At least that is what it seems at first glance.

But if you take a closer look, it will turn out that Belarus is what we make of it. For example, in Gomel the TemaVIDOS girls started making their own video series and film sketches on lesbian life. Also, there is now a society in Gomel called “Gender Investigations” where people can discuss books, stereotypes and personal experiences.

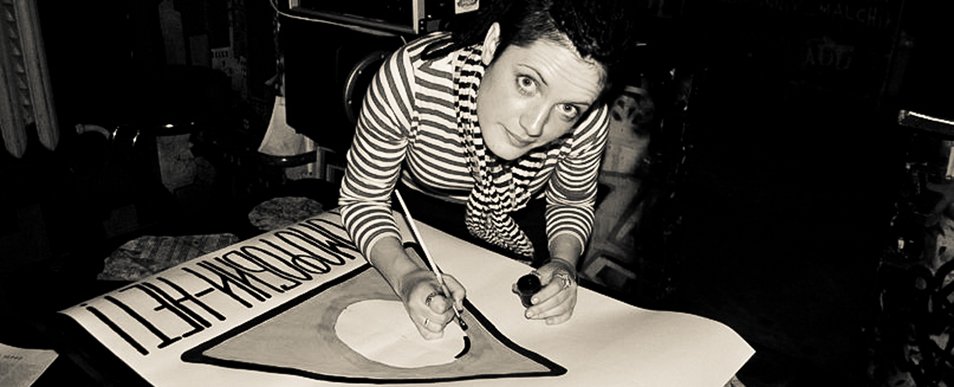

Not frequently enough, but quite regularly representatives of various initiatives from the capital come to regional centres: MAKEOUT has brought our film club to Babruysk, Vitebsk, Grodno, Gomel and Brest, the DOTYK queer festival has come to Brest, Grodno and Vitebsk.

Apart from this, initiatives emerge in the regions that are not directly related to the LGBTQ community, but are of great significance for developing useful competences and democratic solidarity. One can learn about such projects in one’s town and look for like-minded people there. Social and traditional media may present you with most interesting announcements and opportunities as well. For example, the youth magazine 34mag has a whole section called The Province that is dedicated to life and events outside of Minsk. It contains a fairly large number of publications and is regularly updated.

One can’t say that living outside of Minsk certainly means dying of boredom and heteronormativity. As practice shows, if people are ready to cooperate, put time and efforts into building a community in their town, then they will certainly see results. We are different, but it is important for us to receive a positive socialisation experience and support, to feel that we are not alone. And when you are not alone, it’s already like laying a steady foundation, the foundation of support, trust and opportunities.