What did the Panikoūka mean to its frequenters? What did they hope to find here? What made them come here every day on the clock like it was their job? And finally, why did it all disappear?

The choice of place for the interview is deliberate and symbolic. We are sitting over the place that used to assemble Minsk’s diverse queer crowd for several years. It is the Alexander Square, known to many of its frequent visitors as “Panikoūka” or “Panika”.

Nobody has been gathering here for almost five years now.

Ania, 25: “This was a place where you always knew for sure that any day of the week after six o’clock you could come here and definitely see someone you knew. Yes, everyone had their own crowd, but they would all gather here at the Panika. Not everyone liked the Panika, but everyone came anyway: some once a month, some once a week and others every day.

That was where I met my girlfriend. It was just the year the Panika was dying… The irony of life! She is not the Panika type of girl, but it’s a fact: we met there. That’s the very essence of the Panika. You may not be hanging out there as a rule, but even if you come once in your life…”

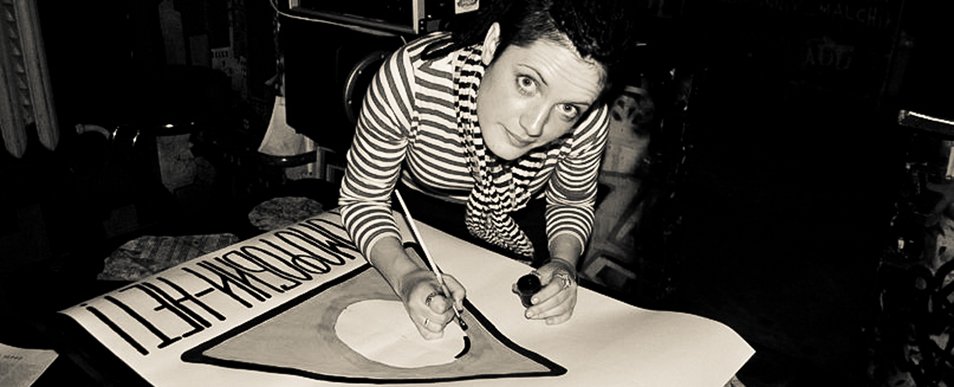

In 2013 after multiple militia raids the first Belarusian gay club ceased to exist that had been called Vstrecha at first, then Nartsiss (Lucik), the last name was 6_A. In 2009 the Babylon was closed. Then a number of other clubs. Now there is only one gay club in Minsk, Kasta-Dziva, which markets itself as a guys-only club (the entrance fee for girls is 4 times higher). Many LGBT-related initiatives and publications stopped to exist too. This piece pursues the purpose to preserve memory and to make the Belarusian LGBT community’s life visible without jeopardising people’s safety.

The Big Wide World

For most people I interviewed, the Panikoūka was the first place where they met other gays and lesbians, or simply the tema, as they used to call themselves.

Lioša now lives in London. He first came to the Panikoūka in 2000.

Lioša, 35: “…It was sort of an accident. I came to the SajuzAnlajn internet cafe and as I was leaving I saw some people sitting there. There it was, the tema, I thought to myself. Essentially, I didn’t know anyone there, but a few people approached me right away, they were quite fun.

It seems to me that it was the high time of the Panikoūka, when I came there. Every night a lot of people would gather. Someone played the guitar, there were always songs, Zemfira mostly. It was very cool because apart from just drinking people were also having fun, playing games. They were making a place for themselves, bringing in the colour in every way they could”.

Some people would come to the Panikoūka in the hope to meet someone, others were already in a steady relationship. Tania, for example, first came to the Panikoūka in the summer of 2003. At that point she had already been dating a university classmate but they lived deep in the closet. Tania describes her first visit to the Panika as going out into the “big wide world”.

Tania, 29 years old: “I’ve been in the tema since 2001 (laughs). No, I knew it about myself long before but I come from a small town where I would sit and think that I was the only one like that in the whole world… Then I come to Minsk and what do you know!

We shared a room with her. And after a while we realised that we needed to consider ourselves something more than friends. That was our small world. We wouldn’t let anyone in our cosy corner, we didn’t say to anyone who we were… For a long time we only had each other to talk to. In September 2001 we started living together, in winter we were already sharing the bed, eating from the same plate, sending each other pager messages saying “heat up the soup, I’m coming home” and so on.

2003, late summer… I went there too. Oh, how cool it was, there was a guitar and a terrifying number of people. They all gathered around me (laughs). We played Zemfira’s songs… Even Tramway [one of Panikoūka’s old hands — Ed.] patted me on the shoulder and said: “Play another one, baby!”

I ask her how many people there were that night at the Panikoūka.

“Well, I don’t know. Maybe around 80. A huge crowd of people!

I could say, that day at the end of summer 2003 was the day we went out into the “big wide world”.

The Panika Is a School of Life

When preparing this piece I spoke to four girls and two guys, one of whom is an FtM-transsexual. Miša came to the Panikoūka once to find people with similar issues.

“… I mean, it wasn’t like it is now. Now you just need to type it in on the Internet and the Wikipedia will tell you everything. There was no Wikipedia back then. There was nothing. So I went to all the Panikoūkas out there”.

Miša, 28: “I hanged out there for about half a year, probably. Last time I was there was in the spring of 2007. There were already fewer people. But I got lucky.

Had I not started hanging out in that environment, I wouldn’t have found so many people with the same problems I was having: there were transsexuals at the Panika too. Later it was already my turn to receive calls from those who had found out about me. They would say “Listen, where should I go, I’m like you”. During the short time that I spent there, I met people and helped others, I think.

Now thanks to the Internet a transsexual can find a community of other transsexuals, not one of lesbians. I still caught the time when I had to go through all that. But I have no regrets. I had fun”.

My other interlocutors also mention quite often that some people came to the Panikouka searching for themselves. For many it was the place where they had their first encounter with the LGBT community. For some, it was the place where their self-identification process actually started.

“The Panika is a school of life. I don’t know what I would have done, where I would have gone, had I become aware of my sexuality now,” says Ania. She first came to the Panikoūka when she was a first-year university student. Before she could feel comfortable, she had to try on different roles.

Ania: “When you know nothing about the tema but you suddenly feel the urge, you can come here, meet people and get some information. I don’t like to put myself into boxes but you go through certain stages in the process of becoming aware of your sexual orientation… How to find someone? Of course, you go through this subculture phase and fall under stereotypes for a while. You realise: somehow being a femme is not in favour, you have to cut your hair and put on pants. I used to have my hair down to the waist before I was 18! I would come and no one would pay attention to me. So I thought: I should cut my hair, put on some pants and become harsher.

It’s a phase when you’re growing up. In a while, once you have gone through all this, you simply become yourself. Confidence grows inside you. When you have some experience, you no longer care about how you look, you know you can be awesome no matter what, even with a plait down to the waist”.

Dress code: “Who is too cool for school/ Who is not too cool for school”

Despite the crowd’s diversity, the Panikoūka had its hierarchy and its own rules. Nearly everyone mentions this.

Ania: “Of course, there was a hierarchy. “Who is too cool for school. Who is not too cool for school”. That shaved dyed shit on the head. The Camelot boots, those men’s pants with pockets. Where did they use to get them? Like, really? I don’t know”.

Lioša: “Of course, there were everyone’s favorites, local stars. And there were our own Quasimodos who everyone mocked and stayed away from”.

As to the girls, the hierarchy here would often build up depending on how brutal they looked. The most feminine of them (they are called femmes) were on the lowest level, and the butches (the most manlike) on the highest.

Tania: “There was still a dress code at the good old Panika. There were backpacks and hoodies or zipper sweatshirts. Short hair. Only a tema with short hair and clipped nails could be considered tema. There were three categories depending on how prominent the “lesbian features” were. There were chicks, also known as “klavas”, there were dykes and butches. “Chick”, “chicken”… When we saw such tema, we would even say as they approached: “chuck-chuck-chuck”. So, a klava-chick, then a dyke — a level higher, and still higher — a butch”.

Zemfira’s Birthday

There were three most important days at the Panikoūka when the largest number of people would gather (by some accounts, up to a hundred and more). Those were the season opening and closing and Zemfira’s birthday when even people from other cities would come.

“Year after year a really incredible number of people would come. Someone would park a car as close as possible to the Panika and put on music. People would bring guitars, stock up on beer and wine. And we used to dance, sign songs, enjoy ourselves”.

Why Zemfira?

Tania: “Because she was our goddess. There wasn’t much choice back then. Basically, there still isn’t. We loved Zemfira selflessly and devotedly. We were always ready to drink her health.

The season opening took place when it was still freaking cold: in April. We would call each other and come… everyone was freezing, so we’d run into the Anlajn cafe every other minute to warm up. The same thing for the season closing: we would already be dressed warm, and it was cold outside, not really a weather for hanging out in the street and playing guitar. That’s how it always was. It was tradition”.

Zemfira’s birthday is, perhaps, the only occasion for people still to gather at the Panikoūka. Today it’s something like a class reunion with ever fewer people attending every year.

Ania: “Efforts are allegedly made every year to come together, but only about twenty people show up. Twenty people! Before, there would be twenty people on a Monday night here! You couldn’t just drop by there for half an hour. You’d spend half an hour only saying hello and another hour saying goodbye”.

The Panika As a Comfort Zone

Ania was seventeen when she became aware of her homosexuality. It was not by accident that it coincided with her first visits to the Panikoūka where she had been brought by a friend. Her first relationship also started there.

Ania: “I came to the Panikoūka in 2005. I was a seventeen, and I was a young girl who wasn’t yet sure about her sexual orientation, so to say. Then I fell in love. And, naturally, when you start dating someone, you become a part of this culture. Hanging out together, going to barbecues, signing songs to a guitar at kitchen parties.

That was how the realisation came. No, I had always thought about this and I knew but… well, everyone around was dating boys… so I had to date them too. I needed to meet social expectations and I tried but something didn’t click inside… Well, that was how I realised it. At first it even seemed to me that I had it written on my forehead: “I’m a lesbian”. I’m on a subway and everyone can see”.

So it was the Panika that was a place where you could come and be with your own without being afraid that everyone would look at what was written across your forehead.

Ania: The Panika was a comfort zone. Well, what else can you do if it’s like that… I mean, where else can you look for a date? Of course, later there was the Internet and all that. But the Panika was a place where you could come be with your own. Certainly, in a year or two you were over it. It was sad when people would spend decades hanging out at the Panika.

Tania: “I just felt like myself there. I no longer had to… I don’t know… sit at the opposite sides of the table with my girlfriend pretending we barely knew each other. We didn’t have to hide anymore. I could drink beer, spit through my teeth, smoke cigarettes. It was this… folly. A completely carefree time. When you could put on your favourite things — be it beautiful and expensive or not at all — and go to the people who were glad to see you. I felt natural and free. It was the richest, the most interesting time in my life… I’ve never experienced anything like that again later”.

Olia and Saša are two of my other interlocutors. Olia, 27, says she used to go to the Panikoūka daily as if it were her job (“… after classes, at six, you get dressed, go out and walk… every day, even if the weather was bad… Everyone else did that too, it was like going to work”).

I ask her what was so special about the place that made them come every day regardless of the weather.

Olia: Well, the people, the conversations, a chance to meet someone new.

Nasta: But you had those things at the university too.

Olia: But that’s different!

Saša, 28: “To me, the most important thing was that I could talk about things I couldn’t talk about at work: how the parents found out, who had what kind of stories… That was very interesting. When you had a question or a problem, you would just ask for advice. And everyone would sit together and think what you should do. Or you’d listen to someone else’s conversations and understand that you went through the same. I had communicated with people a lot even before this, but on the Internet mostly. Here you saw real people and understood that you weren’t alone. That way, through those conversations you’d get answers. Or if not, you'd feel better at least”.

The peculiarity of the Panikoūka was it’s location in the very heart of Minsk, in plain sight. On the one hand, it was easy to control what was happening there, but on the other hand it stood in the way of intimacy, as some interviewees remark. Soon the SajuzAnlajn cafe set up outdoor terraces in the street. Since then fewer people came around (“It was no longer that comfortable with people at the tables right behind you… The place’s intimacy was ruined”).

Tania: “We all depended on something. Everyone was studying, having just left the parents’ house. We didn’t want any problems, didn’t want to get noticed. So when there was someone sitting next to us and watching as we drank and hanged out, kissing one another, even on a cheek… we always were so… tense…”

The Panikoūka’s Decline

Ania’s first time at the Panikoūka was in 2005. In 2008 nearly no one came there anymore.

“It died before my eyes,” Ania says. I think that sounds incredibly sad and poetic, as if speaking of a person. Curiously, I had the same feeling during other interviews. For example, when I asked for how long Tania hanged out at this place, she said: “I remained faithful to the Panikoūka till my graduation”.

Tania: “When I came to the Panika, everyone’s relationships was pretty smooth. Those who’d looked for a partner had found one. Everyone was so calm and peaceful like a lake. That’s why everyone was happy there. And then someone had a falling out with someone else, others decided to make a radical change in life, moved to Moscow or Saint-Petersburg. Someone got into a relationship and closed up in their own little world, happy with the bond. That is why the Panika changed gradually, but steadily. Very young people started coming there… We used to call them “the next generation”, one of them even tried to play the guitar, but they were never… they seemed sort of fake…

We never believed they were sincere and believed in the Panika with their whole hearts, and loved it like we did. One generation faded, another one came, but it was somehow crooked. And it didn’t stay long at the Panika”.

According to the Panikoūka regulars, around 2007 the militia special forces became frequent guests there. That was one of the reasons for its decline.

“They started raiding the place more often. It was those laws: no drinking beer in public places, no gathering in groups of over five people…”

Ania: “Sometimes they would approach just to talk, saying “Look, girls, what do you need this for? Find yourselves a man!” It was crucial that they didn’t run into an aggressive butch. And there were some. There were fights”.

Lioša: “Even while it was still allowed to drink beer in public places, a special forces detail started coming very often. Everyone knew gays and lesbians gathered there and it had always been fine. And then… For what I remember, most frequent were the conflicts between the girls and the special forces because the girls had a more aggressive stance towards the militia”.

Was It Romantic Or Not?

Throughout all the interviews I couldn’t shake the feeling of a light romantic flair that came with the stories about the Panikoūka.

Ania: “Usually, it all happened like this. The Panika. Then someone’s apartment. The kitchen, the guitar, tears. The St. Bernards. I remember this moment as we would gather, all so different, on the floor. This song would play. This effing song. The St. Bernards. You would remember your tragic love, look at your scars. And cry. And think: “What a bitch”.

Yeah, there was some beauty to it. Or is it me, the crazy one, finding beauty in this? There was something apart from the drinking… There was something else. There was a romantic appeal”.

Lioša tells me how people used to spend time at the Panika (“Sometimes people would start playing games or something, I used to just sit and chat with someone”). I ask him what they talked about.

Lioša: “Everything, from sexual escapades to politics. Someone would tell about their new love, someone else about how it was in bed, others about how it was at the Lucik the night before or what book they had read. The Panikoūka didn’t dictate any specific conversations topics”.

Several times during the conversation Lioša emphasises that there was nothing romantic about the Panikoūka.

Lioša: “It wasn’t the most cultured of places. There was nothing high or poetic about it. But it wasn’t about silliness either. This is how young people have always spent time: drinking beer, playing the guitar, talking… Someone would kiss, someone would sit on someone else’s lap. It was a reservation of sorts. There wasn’t any activism or political ideas. The sole purpose was to have fun”.

But then he thinks for a moment and adds:

“No, there was something poetic about it. But it was the kind of poetry, you know, with no sophisticated words… I don’t really believe in LGBT slogans, they are often nothing more than just words. And at the Panikoūka, it was no slogans, no activism, but community life. That’s what the place’s poetic flair is about: there was no politics, none of the ‘let’s stand for gay rights and rainbow flags’ rhetoric".

Those were good times, however critically some people might speak of them now. The Panikoūka is like a mother to us. I’ve always said that”.