Why has the first Belarusian pride parade remained the best attended one? What is the problem with registered organizations and how can tolerance be fostered in society? A talk with Belarus’ first gay rights activist Edward Tarletsky who has been living in Kiev since 2008.

Edward Tarletsky: I think it was 1993 when the organization Stop AIDS Belarus was founded. In the ‘90s, but today as well, I think, the “fashion” was to create gay rights organizations under neutral names. They published a newspaper, went to conferences as a gay rights organization. I was in America back then so I didn’t know them.

Vika Biran: What were you doing in America?

Edward Tarletsky: I lived and worked there for three years. I saw all those gay rights organizations in the States, what useful work they did, I was inspired and when I got back, I suggested to friends we create something of the sort. We thought because it was going to be a gay rights organization, we should have a proper name and charter. In the summer of 1998, we brought 14 people together and held our founding meeting. With protocols, as it should be. And we applied at the Ministry of Justice. The organization was called “Belarusian League for Sexual Minorities Freedom “Lambda”. We actually almost got registered.

Vika Biran: What got in the way?

Edward Tarletsky: I guess the state came to its senses and realized something wasn’t right. Those people from the Ministry of Justice called everyone who’d given their personal data in the registration protocols, they called the people at home and asked: “Is it true that you’ve participated in an organization to promote homosexualists’ rights?” And if the person wasn’t home, they asked the parents: “Has your daughter really taken part in a congress to promote homosexualist and lesbian rights?” That scared a few people away, they refused to go on. My co-chair Sveta Pavlova and me, we went to the Ministry of Justice, brought them all kinds of references, they fucked with us for quite a while and actually showed us the registration certificate, it only needed the official seal.

Then they delayed the issue date, and then suddenly a law was passed that changed the rules for resitering an organization. Before that you only needed ten people, and in the new law, you had to have ten people from each of the seven regions. It was a weird game: one day they had the certificate ready with only one seal missing, and then they went and changed the rules. In the end I realized registration would bring nothing at all. If you get registered, they’ll put pressure on you, they’ll know how to get you. We abandoned it. Because otherwise it’s weird: on the one hand, you say the state is totalitarian and bad, and on the other, you bring them papers for registration.

Vika Biran: How many years were you active?

Edward Tarletsky: Eight years with ups and downs. We’d hold meetings calling them congresses, people would change all the time…

Vika Biran: Was there a great influx of people?

Edward Tarletsky: It wasn’t an influx, it was rather circulation. Some people left, then new people came. There were a lot of people who joined, did something good, and then all of a sudden got the fuck off to some Western country and sent requests from there, like, send us a support letter, we’re seeking asylum. Well, I wrote the letters, I did. I mean, people are free, they live where they want. There was also quite a lot of freaks and people sent by the secret services. We had one activist who was in charge of the website, and he used to run to the cyberspace crime department and hand in log files from our site. I know it for a fact. There were also people who popped up from nowhere, brought apparently fresh ideas and then would suddenly ask in passing, while we were having drinks: “Do you know if there are any of our kind in the opposition?” And then, without finding anything out, they’d disappear.

Vika Biran: What do you consider your main successes?

Edward Tarletsky: We held several notable festivals. Later it became clear that it was impossible to hold street protests, it became ever more difficult. They wouldn’t issue us a permission, but it became clear anyway that it made no sense to ask for it.

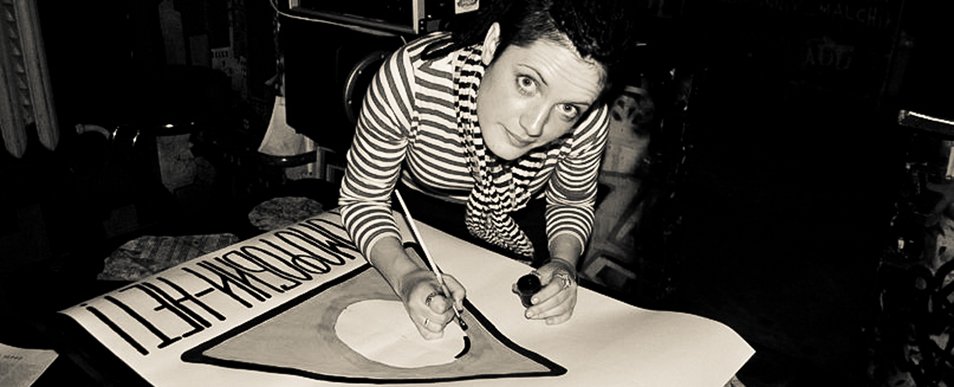

We published a decent magazine. The magazine was the most fruitful, the most familiar and understandable activity for me.

First it was called Forum, and later Apogey. The Forum was even registered with the Ministry of Information for some time.

Vika Biran: Is this why it can now be found in the National Library?

Edward Tarletsky: No, not because of that. The circulation was small, and we were few. It was obvious that we had to fill the space somehow. We’d put it in envelopes and send out to libraries, bibliography institutes, ministries, public offices, non-governmental organizations… We wanted them to read it, to know we were out there. Gay rights organizations cannot do anything by themselves. I didn’t understand it at first and then gradually I grasped it. They can tell people publicly that this problem exists but they can’t solve it directly. You can hold workshops, lectures, but until the government works on the problem, nothing will change. In Russia, they adopted this propaganda law—right, so “gays are bad, we must fucking beat them up”. And homophobic violence surged. On the other hand, there is Ukraine: they invited an openly gay man, head of a gay rights organization, to the Verkhovna Rada. He spoke from the Rada tribune, he described what problems people face. Naturally, stuff like that changes the popular opinion.

Sometimes it’s important to go out and say openly: here I am, and I am what I am. And sometimes that’s enough already.

Vika Biran: In 2001, the first Belarusian pride parade took place. How many people participated in it? Different sources mention different numbers…

Edward Tarletsky: We walked from the circus building to the President’s Administration, it was a short route… (remembering) The police who were there referred to about 1,500 people.

Vika Biran: It was so many years ago, so why does that parade still remain the best attended one?

Edward Tarletsky: I don’t know. We did it together with Belarusian informal leftist groups: antifascists, anarchists, and called it a love parade, not a gay pride parade. We never filed for state permission and emphasized that it was an unregistered organization, an unsanctioned demonstration. We emphasized that stance on stickers, leaflets… We didn’t suggest any political slogans but sewed flags with flowers on them. I guess people liked that approach. There were two gay flags, one was large, and I actually walked with a pink flag. The Internet wasn’t as well developed back then. I was afraid no one would turn up at all.

Vika Biran: Do you have any unfinished gestalts left that are still nagging you?

Edward Tarletsky: I had this idea to open a community center in Minsk. Girls have other problems, of course, but boys usually meet at night clubs, drink, and that’s it. We wanted to make a social center where people could come during the day to talk, organize a singing group, whatever… We didn’t do it because it was impossible.

Vika Biran: Do you think it’s still impossible?

Edward Tarletsky: Of course it is. Once again, until the state sends some kind of signal.

Vika Biran: What was the most difficult thing in your work?

Edward Tarletsky: After I announced I was gay and head of an organization, most people who I was friends and worked with—and I was working for the Radio Liberty back then—turned their backs on me. They stopped talking to me, saying hello. One former colleague, a famous journalist, washed coffee mugs with bleach after me. Probably to reinforce the castoff image, they called me a “KGB agent”... And then I couldn’t even find a job, no one would take me. They’d say: “Edik, we’re famous as it is”. So I created jobs for myself: thanks to that magazine, I started performing more as an artist.

Vika Biran: So you actually started from scratch, didn’t you? The only ones before you were the Stop Aids people, is that right?

Edward Tarletsky: It appears so. But they did useful work too. They published a newspaper where they advanced the idea that gays weren’t the primary AIDS carriers. Because that was the propaganda back then: AIDS is mostly a homosexuals’ disease…

Vika Biran: Do you think there is an LGBT community in Belarus, I mean specifically as a community?

Edward Tarletsky: No. There are no communities in Belarus, therefore to speak of an LGBT community is ridiculous. There is the state, there are small political parties, and there are people, and they all exist completely separately from one another. And if the people get together to get something done, they are few and they have no idea how to find connections among social groups. You know, I’ve always been accused of some kind of radicalism, of being inflammatory. The line those people pursued went something like this: “Just stay at home and fuck each other, we’ll hold a party for you at some enclosed location, and God forbid anybody comes from the outside, stay among your own and don’t make waves…”

Two organizations that have always supported us and haven’t been ashamed to admit it, in Belarus or abroad, were the Viasna headed by Ales Belyatsky and Alitsia Shibitskaya’s United Way.

Many human rights advocates and representatives of all kinds of parties said they supported gays while they were abroad, but in Belarus they were too prudish to speak up.

Vika Biran: Do you feel anything has changed during these fifteen years?

Edward Tarletsky: I don’t know. I think it even got worse. After around 2001 we established contact with anarchists and Belarusian antifascists, and together we held a lot of protests. I started to mature then and now I’m completely sure: in a climate like the one in Belarus, it’s wrong to ask for any kind of registration from the state.

Vika Biran: Do you plan to come back at all?

Edward Tarletsky: No, never in my life. (Laughs.) Well, first of all, after how they bullied me… Especially during the last two years, all kinds of public structures. I thought afterwards that even if democratic transformations started, many years would have to pass before people would actually change.

I went on a trip once, I come home, I enter my apartment, I put my suitcase down, and in precisely fifteen minutes the local police officer is at my door. And he says: “We’ve been looking for you for so long, we’ve been waiting.” I say: “Alright, come in. But tell me, how did you find out I was back anyway?” And he’s like: “We asked your neighbor to call us when she heard you.” And the neighbor was twenty five, by the way. Well, and then all the atmosphere in Belarus… I have no idea how you can live there.

Vika Biran: How did you decide to leave?

Edward Tarletsky: I was given a cue that I should. For years they couldn’t pin me down for anything, they couldn’t punish me for anything, but then in 2007, I had the poor judgement of starting a busines and opening my own club called YoYo Buffet. That was a mistake. I had a business partner, he suddenly left the business, and the Oktyabrsky district court started making decisions that made my property belong to no one, that is, to the state. I appealed at the city court, it reversed the judgement, and the Oktyabrsky court decided against me once again, and it all repeated. Finally I got so fucking tired that I decided I had to leave. And meanwhile, the good men from the KGB offered me to participate in yet another Belarusian TV project where I was supposed to tell about who in the opposition had non-traditional sexual orientation. I remember one phrase very well: if you cooperate with the state, the state will meet you halfway. And everything will be fine in the Oktyabrsky court. “But why me?” “Because, Edik, people will believe you.”

During my last years in Belarus, the pressure on the part of the state was huge. Strange people would call all the time, approach me on the street, invite me to talk. Those state representatives often said to me: you should leave, you’d do better to leave.

Even now I still don’t get what danger I posed to the system. By the way, the officials who put in the most effort to fight homosexuality and our organization happened to be those whose children were not just, as they say, representatives of non-traditional orientation, but were and still are the true spawn of Sodom and Gomorrah, the most depraved of beings! But I had nothing to do with them. I didn’t make them into faggots.

Vika Biran: Why is at that all activism in this area mostly represented by men’s names?

Edward Tarletsky: The general atmosphere in the society is patriarchal. I mean, how many women’s names are there in Belarusian politics as a whole? And if we look at other countries’ experience, women sometimes play a crucial role there. And Belarus stays a patriarchal, prehistoric society where they probably still disapprove of single mothers. Every gay rights movement mirrors the general picture of what’s happening in the society. Women don’t participate in Belarusian politics, they sit at home, and it’s the same with lesbians. There is no civil society in Belarus, so there is no gay community either.

Vika Biran: What do you do now?

Edward Tarletsky: I work as a travesti artist or drag queen, and I also work for a stage outfit making company. I partner with a human rights organization in Ukraine…

Vika Biran: Have you been invited to perform in Belarus? In any function.

Edward Tarletsky: I don’t want to anyway. That’s my fundamental stance, I don’t want to go there. Either to live or to work.

Photos: photo.bymedia.net , gay.by and courtesy of the protagonist.