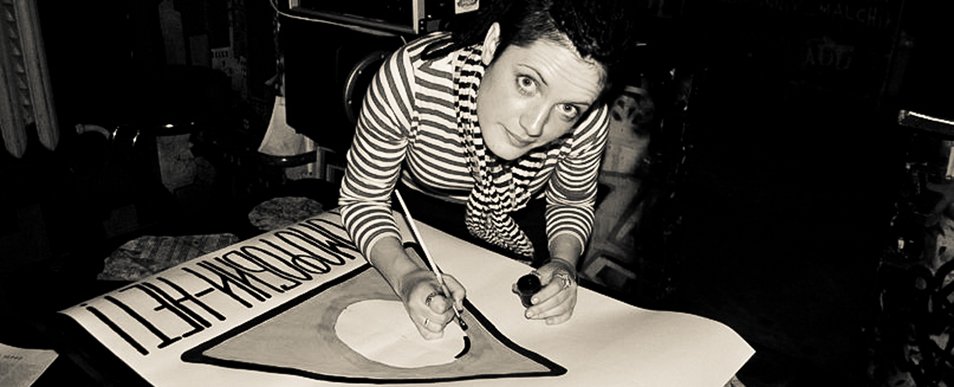

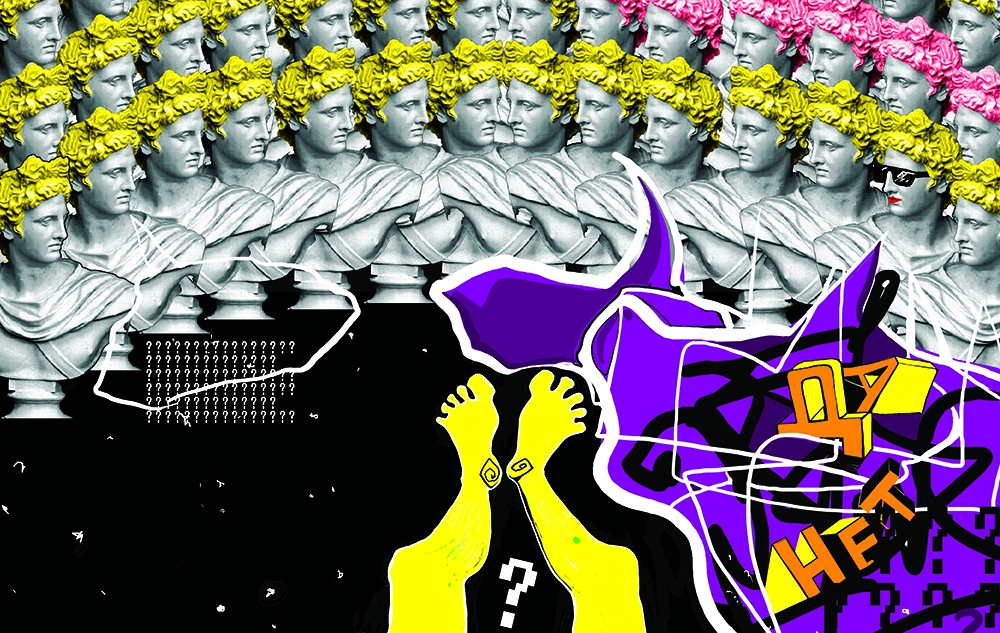

TemaVIDOS is a creative team that, according to the members, produces “parody, absurdity, slapstick, freak show, and a little bit of grotesque for our own.” This interview was recorded in early 2016. The team happens to have partly changed its makeup since, but we decided collectively to publish it in its initial form.

Veta: Some of us know your faces as well.

Nastya: You snitch! We’ve been doing this for a long time and we’re going to continue while we’re alive and well. And that we’re going to be until we’re old, unfortunately—in a country like ours you have to say unfortunately.

Nasta: And when it was all starting, how did it start?

Nastya: How was the steel tempered? Me and Masha, we’re both from Gomel. I was born there, Masha came there to study. We started filming in Gomel, back when we were living there. Back then, there was no Internet at a scale that we would all be online. Some didn’t even have a phone, I guess, let alone Internet. While you’re being bored, Masha, why don’t you count how many years ago it was.

Masha: Around 10 years ago, maybe. Tell them how we filmed The Dinner Party—it was your idea, after all.

Nastya: At first we just wanted to have a laugh, we filmed it on a regular phone. There was a girl in our friends group… At that time nobody really had a whole apartment for themselves. But she did — one of her own! And of course, one day we were having tea and decided we needed to make a joke. Everybody said: “All you do is talk, it won’t go anywhere,” but I was really excited about it. A couple of days later, I called our common friends together and we made the Dinner Party. The Internet wasn’t that big a thing: some of us probably had an account on Vkontakte, a collective one. So we posted the video there, it was only meant for the other friends who weren’t able to come on that day. But then other people started to watch it, friends asked for more, so we made another one. A whole network grew out of it, and absolutely strange people started watching too. That’s how it became more than a hobby, it became our whole life.

Nasta: Was it already a series, or were you just making separate videos?

Masha: At first they were parodies of TV shows.

Nastya: All kinds of TV shows.

Masha: It made sense: because we made The Dinner Party, next we had to make—what was it? The Fashion Verdict, The Field of Miracles—that one was terrible, admit it!

Nastya: Well, the original show is terrible, so it follows that the parody must be terrible too.

Veta: There was the Psychics Battle too.

Nastya: We also made parody infomercials, with no reference to anything.

Masha: Why did you decide to make a TV series anyway?

Nastya: I really wanted to make a series. Because it’s long, it’s interesting, it would show our life. With a one-time show, we can only make small parts of it visible, but with a series… If we take all those things away, if we just sit down with every person in private: “You know, I onсe had this and that happen to me”, stuff comes out and you think: wow, this is a series. Another person tells her story, and that’s a series too. Every day is an episode.

Masha: You know why I like series best? They tell you all the time: “Go on.”

Nasta: You say life is a series, and if people share their personal stories, this makes up a whole series. Does this mean the plot is based on personal stories, on personal experience? Where does the plot actually come from?

Nastya: I’m sorry to say this, but the nastiest videos, the nastiest facts there are all based on our lives. This is what our homosexual life looks like from the outside. These are the stories that happen around us all the time, however horrible they might be.

Many commentators are like: “Urgh, this can’t be real!”, and you have a look at the person’s own page and think they are exactly someone this could’ve happened to.

Our life is different from straight life: much as we would like to adopt a dog, to hang a painting on the wall, to have someone read their newspaper next to us, nothing of it will happen anyway—our life is different.

Nasta: There is a lot of humour in your stories. Is it rather like mockery?

Ruslana: It’s an exaggeration, a hyperbole. To make everything look larger than life, to make it more understandable, more interesting. If we’d made it look more like everyday life, many wouldn’t have got it, would’ve misinterpreted it. I wasn’t part of the older videos so I’m telling you my thoughts now. Back then, it seemed like the girls were just making fun of themselves, turning themselves into ridicule… I mean, there’s a lot of antisocial stuff there. Some people think that’s what “thematic” life is. So the series shows exactly that, only exaggerates it ridiculously. But it shouldn’t be taken seriously, I mean our whole life is humour.

Nasta: Do you mean it is an element of self-criticism?

Nastya: It’s self-irony. It makes it easier to look at your life, easier to live it. When problems arise, you look at it as if from the outside, as if it were a movie. That’s what I personally am used to doing, and now the whole team is too. You look at yourself, and then you push the problem away from yourself, you take a detached view and you see it’s actually funny. And when it’s funny, it’s not a problem anymore. You can tell people about your problems and laugh. Aside from our shared passion, we’re all friends. And when we talk about our problems—if you heard it, we would be ashamed… We cry with laughter.

Nasta: Can you say who the series is about? Who are the characters?

Nastya: Are you sure you’ve seen it?

Nasta: Yeah, but how do you describe them for yourselves?

Nastya: I get that Minsk is probably more refined, but in other places, people are not like in Moscow or Minsk. They don’t go to the B2, they don’t drive BMWs.

They stand on benches and drink beer—and those people also have feelings, they have love. Their life is what it is.

And the smaller the town… Even in Minsk, we have to deal with this thing: “that’s my ex’s ex, that’s my future one with my ex”—you get that even in bigger cities, so imagine what it’s like in small places. So the series is about those people, the regular ones, who go to the grocery store, come back home, make friends within their own closed circle, obviously.

Masha: And I don’t get how they’re different from “straight” life, like you said: they do the same things, they come home, they light up candles, they make romantic dinners.

Nastya: Okay, you don’t have your role anymore. (Both laugh.) Our life is different: we don’t make plans for the future, even if we’d like to.

Veta: Ouch! That hurts.

Nastya: I know, everybody always says that’s not true, but really, if you look inside yourself, there’s always this razor’s edge: either you’ll slip or you won’t…

Vika: How did you find each other? You and Masha met in Gomel, you’ve already said. Ruslana, and you said you’d already seen the videos. What contacts made your paths intertwine?

Ruslana: Overall, I spend little time on the Internet. The girl I was seeing back then watched the series, and I saw a couple of videos with her. And after many years, they found me, through a chain of acquaintances.

Masha: When we came to Minsk, we knew no one. We had a role and were looking for a specific person—we knew what the actor was supposed to look like. And through some people we knew, we found Ruslana.

Veta: That was the only casting we ever had.

Ruslana: They wrote to me and I already knew what it was about. I like interesting stuff anyway, so we met, and that’s how it all started.

Vika: Will the cast stay the same from now on?

Veta: Rather, it will expand.

Nastya: People will come and go but the core will stay the same: it’s us and one more girl who you know as Yola or Lena. She has always been with us and always will be. If someone among your readers wants to join us, they shouldn’t be shy to contact us.

Vika: And how did you move to Minsk?

Veta: Nastya was studying here, Masha moved three years ago, and myself six years ago.

Nastya: It just happened.

Nasta: Do you think you moving will affect the series?

Ruslana: If you’ve seen the previous series and the new one, you can see the difference. The style is the same, but it feels different.

Masha: And it hasn’t become better.

Nastya: It hasn’t become worse either.

Ruslana: My friends like this one better.

Masha: Mine ask me why we mess up so much in this one.

Veta: The audience was larger before, there was a whole group.

Vika: I think it happens to all projects: when you deliver episode after episode, a lot of people come to you, and then if you stop for a while, some things need to be repeated. I think it’s nothing to worry about.

Nastya: I think so too, especially as we have re-formed the team now.

Vika: What about function allocation within the team? Who is responsible for what?

Ruslana: Do you mean who is the boss?

Nastya: Where mispronounced phrases are needed, that’s Ruslana speaking. (All laugh.)

Veta: Nastya is the motor.

Ruslana: I’m an actor.

Nastya: We think everything through together, Masha thinks through a lot of things. Veta does the camera work.

Vika: And who writes the script?

Veta: Nastya does almost everything.

Nastya: And before every filming session…

Ruslana: … she gives us a small chocolate!

Masha: Yeah, we work for food.

Nasta: You said the project then and now are two different things. But what’s common, is there a connection, something important you took from there?

Nastya: This is life. We film it how we live it—that’s what has passed on from the old one. So have the types of people: you can go to four different clubs, to Piter or to Moscow, and still you’ll see the same types of people.

Nasta: What about the characters?

Nastya: The topics have passed on, but the characters will be different, of course. The thing is, over the three years while we weren’t filming, TV took a huge leap. And we’re a parody team, aren’t we? We borrow from TV, we follow it. So there will be parodies of the TV series that are running now. For example, our project’s first episode and the whole idea, actually, is based on this new show, Hot and Bothered, about people who get visited by relatives from the countryside.

Masha: That’s an extremely cheesy Russian show. Our first series was like TNT’s Real Dudes, this one is like Hot and Bothered…

Veta: And like the The Best Day Ever movie.

Nastya: Naturally, there will be short videos too—they have nothing to do with the series, so that those who don’t want to watch the series won’t “have to watch it” because, like, “there’s no L-comedy, we’re dying without humour in the CIS.” You don’t want the series? No problem, we’ve started to make 30-second small ones, like they make them abroad: all those “10 reasons” and so on. There will be movie parodies too.

Vika: Have you already received collaboration offers, offers of support?

Nastya: Just the right time to ask us about the honeypot! There was one, from foreigners, and it was so sleazy and dodgy that I didn’t take it. Now that I’m older I think: maybe I should’ve bowed down… But I didn’t want at all to bow down to anyone and lose face for money, doing what they wanted us to do. (Editor’s update: In the summer of 2016, TemaVIDOS went to Vienna and that was, quite to the contrary, a 100% positive experience.)

Vika: Do you mean they wanted to commercialize you?

Nastya: Yes. Not that they actually showered us with money—they fed us with empty hopes first and then started to pressure and pressure us… But I didn’t want to change our line. It was a negative experience because they were sneaky people. For example, they didn’t know I could understand English pretty well, and they mistranslated what I said.

Masha: Did they pretend like you were saying you were being oppressed in this country?

Nastya: Something like that.

Ruslana: You want to do what you do and have fun with it. It hasn’t been for profit from the start, it has always been about self-expression. And when you’re being required to do things, that’s more than an idea: everybody wants to get something from others. But we and them just were a bad match.

Nastya: But we went to perform before the Swedes in Kiev. Imagine that, before the Swedes in Kiev! We’ve got this one video, it’s called Coming Out, it’s that whole situation that is satirized there. I’ve been around in those dealings for a long time, since I was around 18 or 20, and I’ve seen how it all gets done. The higher people’s status, the less they care about how people live down below. But that Coming Out video—the Swedes laughed. Because it’s true, that’s how the system works. And then they talked frankly to us, they took their masks off, it was interesting.

Nastya: We need to deal with everything ourselves, we need to fight homophobia here ourselves, we need to behave well at work, because at work, they judge all lesbians by looking at us…

Masha: Why do you show all lesbians drinking then?

Nastya: But I show it to ourselves! That’s part of the humour.

Ruslana: People can look at it from the outside and realize that it’s absurd and that instead of having another drink they’d rather go and study something.

Vika: How do you define your target audience? Is it “members only”?

Nastya: 18+, otherwise everyone’s free to watch. We have a lot of heterosexuals in our audience, a lot of men—everyone has a laugh because everyone sees it in their own way. I mean, we don’t show tits or pussies in our videos: you can think it’s just sexless acting, just people, like in the Sweet Little Town or something. I mean, there are also specific jokes — like if we say something about butches, nobody else will get it…

Ruslana: There are universal lines in the plot, they’re suited for heterosexuals as well as homosexuals.

Nasta: What about within the team, when you think through the plot, do you envision those who watch you?

Nastya: When we write, there are some jokes that are horrible, the lowest of the low. It’s mainly me. The girls say to me: Nastya, people will simply turn their computers off, they’ll simply bang their laptops down, let’s class it up a little. So we start to turn them over so that everyone can get them: those who wear down jackets, those who wear fancy scarves or coloured coats.

Masha: People who have little space for humour in their lives, very serious people don’t like our videos. They don’t pick up the context, they look at it superficially: “Why are they all drinking, cheating, why are they all ugly—couldn’t you find pretty girls?”

Vika: In what form do the criticisms come then? As comments?

Masha: They write: “I’m ashamed of you.”

Vika: Are they lesbians, those who write that?

Masha: Yeah. They must be very sophisticated because they say something is out of focus or that the logos we make in the Movie Maker are ugly…

Nastya: Well, they used to say it about the first ones, now the quality’s gotten a lot better.

Masha: Now they just write we’re degenerates.

Veta: That’s a quote.

Masha: A person with Zemfira on her avatar writes: “Couldn’t you find anyone prettier?”

Nastya: Well, Zemfira is prettier than us, isn’t she? Maybe it was actually her who wrote it!

Veta: I knew she’d write to us and find me!

Vika: We just read the comments today, they’re mostly very positive. Did you delete something?

Nastya: We never delete anything in the group. Like Dalí said, “let them talk about you, at worst let them speak well of you.” I mean, people don’t actually mean ill, they’re just sort of defensive—it’s fine, it’s their opinion, that’s the reason why we’re all different. They say nasty things and click “follow” right away.

Ruslana: Many come and say it’s all pathetic and poorly made, but I always think: well, do it better! Every mobile phone has a camera nowadays, go on, film something, make yourself look prettier, make your flatmate look prettier, show us what you’re capable of, then we’ll talk. Let’s be realistic: if you can do better, go and do it, why criticize?

Masha: Well, I like to criticize too, and I can criticize things I don’t know much about. Do I have to write a book to be able to criticize someone else’s book? No, I don’t! Belinsky didn’t write books, he just tore down other people’s.

Nasta: There is the word Tema in your name. What is it actually about: women, homosexuality, lesbians? While watching your videos, it strikes one’s eye that there are no male characters at all. And even though you say that your videos may be watched as “sexless”, they are about women’s lives. Is that important for you?

Ruslana: Let’s be realistic: how do women live around here? At twenty, you get married, at twenty five, you have your second baby…

For me tema is about lesbians only, it’s a girls’ sexual world.

Nastya: That’s why in TemaVIDOS, there’s more tema than vidos.

How is our context different from foreign videos, even the ones made in Piter? In Piter, you can go out and ask: “Who wants to act? Will you come? And you? And you?” If this one is scared, the next person but two will be your actor. But for us, it goes like: “Girls, do you like it?” — “Yeah, we do.” — “Are you ready that your mom or you brother might see it?” — no, not all are ready, far from it. Many say: “I’d love to, but I mean, everyone will see it.” People work at factories, mine used to work and still work at a plant, one of them mastered herself and came out but… In Belarus, people are afraid, they go to the grocery store looking over their shoulder, let alone acting in videos.

Some would like to act but don’t want to do what I’ve written in the script, don’t want to play such characters. But it doesn’t work like that. True, we’re all friends, we have fun while we film, we enjoy ourselves, there’s no coercion, nothing like “abandon your shift, come in your work clothes” and so on. We discuss things, we meet when everyone has free time… But we have responsibilities to each other. It’s not like you can come and say: “I want to do this but not that.” Each of us is a team member, each of us acts: we know we’re going to share the common cause regardless of whether we like those clothes, that partner in a scene. We accept from the start that it’s filming, it’s a video, so it’s okay if someone puts her arms around you or you look weird.

Milana: How do you distribute the characters among yourselves? When the script is being written, does someone say: “I feel like that’s my evil alter ego, I’ll play her,” or is Nastya the strict director who assigns all the roles?

Masha: Because we’re still so few, we have to take it into account while writing the script. Sometimes a role is written with a specific person in mind. For example when Nastya says we need someone “big and scary”, we don’t have anyone like that, so it’s Nastya who’ll have to pull a scary face, put on a funny hat. But in the previous project, the characters were written first and assigned after.

Nastya: As a matter of fact, I don’t give people a choice. It’s my acting team, I’ve put it together to work. If actors start to go through my notes and pick whatever they like, no decent work will be possible. They must hear the director and do what they’re good at.

Masha: It only worked with Ruslana: there was a character written and we were looking for a specific person.

Nastya: When I write the script, I see the movie immediately, the video we’ll have in the end. And if I begin to doubt whether something is right, I sort of go back to the scene in my thoughts, as in rewinding. It makes no sense to think about who will do what: I already know what Masha will say and how, what clothes Ruslana will have on, at what angle Veta will position the camera.

Milana: When I watch the videos, I notice classifications, the character types are an important theme. But what role have they played in your own lives? The words butch, dyke, femme—is it a Belarusian thing to you?

Nastya: I think it came to us from abroad, it’s foreign. You write yourselves about hordes and thousands of weird terms, don’t you?..

Ruslana: You’re getting off the point. What about the classification within the L? I mean, it’s world old, I actually have no idea where it came from.

Masha: But nobody wants to inscribe themselves into it anymore, do they?

Ruslana: Because nobody wants to be a cliché, everyone wants to be unique. In fact, everyone understands more or less what type they belong to—with time, it all became very clear in the videos.

Nastya: Well, it’s about the types of people.

Milana: I’m thinking rather about the short videos, about those captions saying Butch, Dyke, about the matching decor. How much irony is there to it, and how much earnestness? How do these words work for you?

Nastya: You’ve seen the comments below the videos, haven’t you? Butches post photos of themselves there and write: “The same thing happened to a friend of mine.” They are real people. It’s like movies: they’re good because you watch them and think: “Wow, it’s like my life.” That’s the catch. It’s part of our life.

Ruslana: Our looks have a lot to do with our personalities, but still, it’s all very relative: if I’m a butch it doesn’t mean I don’t like flowers. Remember how the L Word got out and everyone started to classify themselves and imitate all the characters. That was exciting! It’s like my teenager years weren’t for nothing!

Milana: How do you feel, do people often recognize you in the street?

Masha: Yes.

Nastya: They do. I went to Ekaterinburg once, went to a nightclub and someone came to me, pushed me in the shoulder and said: “It’s you!” Then I was visiting friends in Perm, not far from Ekaterinburg, we met in person for the first time and they’re whispering among themselves: “Do you know who she looks like?” And then they tell me who I look like. “Only that one is a bit prettier than you.” Recently someone recognized me at a public bathroom. We had another project that had nothing to do with the tema, it was about Gomel, about a mother and her daughter who discussed local news. Local media wrote about us because of it and people recognized me and the other girl who acted there, Olesya.

Vika: I haven’t been living here all my life either, I came to Minsk when I was 17, when I went to the university. And in my experience, the word tema means lesbians who used to hang around at the Panika, in the Babylon, back when there were all those closed friends’ circles. To me, it’s a word from those times that were before me, and I don’t use it often, apart from jokes like “typical tema” or “tema philosophy”.

Nastya: What about you lot, is tema a thing to you now?

Masha: To me it’s an old word too. I remember, when I was 17, I came to Minsk for a Surganova concert. I stayed with a girl I met on a dating site and she says to me:

Маша: Для меня это тоже старое слово. Я вспоминаю: когда мне было лет 17, я приехала в Минск на концерт Сургановой. Вписалась к девочке, с которой познакомилась на сайте знакомств, и она мне говорит:

“Don’t say lesbian, you must say tema.” I’m like: “Why?” And she says: “That’s the only term tema’s use here.”

It’s that sort of memory for me—I remember I took pictures at that concert with a roll-film camera. It was such a long time ago…

Ruslana: It’s old alright, but it does provide excellent camouflage. You talk and people around you don’t eavesdrop when it’s not okay.

Masha: Okay, in what context should we use this word? “She’s in tema”—why can’t I say “She’s a lesbian”?

Ruslana: Because it’s no fun when you have to fight off a drunk guy on the street who heard the word “lesbian”.

Nastya: We also say: “She’s—yes?” Or “She’s … m-hm?”

Masha: She’s “yes”? We could make a “Yes-VIDOS”.

Ruslana: Tema is a protection word, it’s our-world-word. I like it.

Vika: Which one would you prefer: for you to be comfortable within the project, enjoying making every episode, or for something to change around you, considering the topics you bring up? What weighs out for you in the project?

Nastya: Oh, it’s obvious we’re supposed to choose the latter. Of course we want things to change, so that lesbians tumble out and run down the streets in white fluffy dresses, and that they’re served whisky and then they answer: “No thanks, we’re fine, we’ll have some green tea, without sugar.” But the truth is nothing will change.

Masha: Why not? I mean there is no messianic function here. It’s actually very simple: when you live in the countryside…

And I, for one, was born in the countryside—until I was 15, I thought lesbians only lived in the Netherlands and I should slash my wrists right away and die because I had no idea how to get there and no chance to get an American visa.

And then you listen to Zemfira’s first album, and it starts with the line: “I burst into your life and you were stunned.” You think: wow, she lives somewhere not that far away, doesn’t she, somewhere in Moscow maybe! And then you watch TV and a few women even appear in a Brazilian show, and you think: damn it, Brazil is far away, of course, but they’re actually in a show, right on TV. And you feel better. And if people in Belarus are shown Belarusian girls who work as crane operators and aren’t afraid to show their faces, I think it will be easier for people. It makes their lives a bit nicer, even if it’s badly made, that’s not the point. The point is that it’s our people, that it’s not all in America, it’s our jokes, our realities. And they’re exactly as they are in real life, unpolished, tousle haired…

Nastya: They’re regular girls, “girls like me”.

Masha: And people feel better. Especially kids, those who the 404 project is made for, the one that they’re trying to close down all the time, tormenting Lena Klimova. I remember myself at 15: I was hurting because I had no Internet, nothing. My life in my village sucked, and then I grew up and found out I wasn’t the only one in my village.

Nastya: When we first started filming, we began to think: what can we watch anyway, what stories are left for us? If we type “LGBT movies” into a search engine, we’ll see someone dying of cancer and everyone crying, or of AIDS…

Ruslana: Well, that’s a global problem, isn’t it?..

Nastya: Yes, but it’s a recurring story, all the time, endlessly—gays and lesbians suffering and dying. There was no humour before us. But really, it’s like Masha says: our poor downtrodden Belarusians, and this “it can only be somewhere far away” attitude. And then people somewhere in the middle of nowhere watch it and think: wait a minute, it’s actually okay.

Ruslana: That’s right, have you noticed how almost all movies about LGBT are about hard lots and suffering… There’s a lot of negative and hard stuff. If you see it as a teen, you project it all onto yourself: that you’re going to have a hard time, that it’s going to be scary, that you’re not normal, you’ll never be happy, you don’t deserve happiness. That’s why there is a need to laugh and mock: so that you can see that in fact, everyone’s life is not all honey, in every life there are breakups and cheating. But that can be funny too.

Nastya: As with all comedy in the world, there is a psychological function to it, it’s sort of about helping people, easing the tension.

Nasta: Tell us about your next plans.

Nastya: There will be short videos, parodies… We wanted to make a parody of Let’s Get Married because it’s such a horrible show… The series will be short so that nobody falls asleep while nibbling on sunflower seeds: 10 or 15 minutes. If we want something more serious, we’ll make a real big movie, but that’s very long-term plans. First we need to make sure we have both feet on the ground.

© Photos and videos courtesy of TemaVIDOS