I interviewed three Belarusian queer artists and talked to them about art, identity and life in Belarus here and now. Because visibility is valuable.

Art is a way to share your view of the world, and if you don't see the works of people with an experience similar to yours, it seems to you that it is illegitimate, that there are some universal experiences of a heterosexual cisgender man from the First World, and the ones that you are facing don't matter, that they are your individual problems.

How many Belarusian female artists do you know? And Belarusian male artists? Russian information field constantly engulfs us as a shard of the empire, and I hadn't known almost anyone before I started making art myself.

So for me, these are very personal conversations about a painful subject: how to live, how to speak about yourself with your own language when there are not so many opportunities to be heard.

I interviewed three Belarusian queer artists and talked to them about art, identity and life in Belarus here and now.

Because visibility is valuable. The larger your audience, the more likely it is that someone will buy something from you, or invite you somewhere, or offer something. This is valuable for survival in a market economy. And from an emotional point of view, it gives validation, new strength and inspiration.

Yana: Introduce yourself :) Tell us about yourself, about your identity, how do you want to be seen? Can you call yourself a queer artist? Do you consider yourself an activist?

Vika: Yes, I consider myself a queer artist, a queer activist and a queer person. I usually say that I am a non-heterosexual, non-monogamous and non-binary woman, and all my identities challenge the status quo identities. It is important for me to use art as a form of activism. I intentionally choose to utilise political and social optics in my art.

Yana: Where do art and activism begin and end? When does art become activism, etc.?

Vika: For me, this is a question of defining yourself as an artist, of setting priorities in art and your work. I believe that all art is social and political, even portraits and landscapes at the autumn salon, because even if they do not say much, we still understand the conditions in which they were created. Art is activist when you consciously work with social and political topics.

Yana: Tell us about your creative history. When did you become interested in art and realize that you wanted to make it? Where did you start? Have you studied somewhere?

Vika: I went to an art school in Vitebsk. When I was a child my family always said "Vika is a creative person", but I never finished that art school. I imagined that I would move to St. Petersburg, I would live there in some shabby apartment, drink wine with my partner, go to an art university and live the life of a "unhinged artist" to the fullest. At that time, I was not on good terms with my femininity, and my role models were some men, and I think that this role model was also one of a male artist: he is over forty, fucks with everyone and gets by on the last pennies.

I chose where I would enroll to in two days, and then I got a degree in culture and management studies. I chose this major because it didn't require math exams, completely forgetting about my identity as an artist. Only by the end of the first year I slowly began to do something, but it was difficult for me to call myself an artist, even in my mind. And when I talked to "important" people, I felt as if I'm just a little girl who makes pictures. As an artist, I felt as illegitimate as possible. I started to believe that I could call myself an artist maybe only two years ago.

© Vika Grebennikova, "Card for the partner"

© Vika Grebennikova, "Card for the partner"Yana: You mentioned collages, and what other art techniques do you use? I know that you also makes zines [independent small-circulation publications — editor's note].

Vika: Collage is the safest material for me, I know how to work with it. But I want to try a lot of different things. I made my own zines and one collective zine about sex and environment; I made linocuts, a digital collage and also wrote a vocabulary for it. I think I've already accepted that I'm a visual artist. I also like to write all sorts of texts, but I feel awkward about it because "who am I? I'm not a journalist, I'm not a writer" — I still don't really understand what this is and what I should call myself. Zine is a very favorable tool in this regard, because you can do whatever you want, you can draw, write, and stick things together. I made the third zine called "Social Art" somewhere at the peak of the protests: I used a lot of film from the queer block when we took to the streets on Saturday the first time. There are photos, a little digital art, some text, and everything is arranged.

Yana: You said that you don't like interacting with institutions. Have you ever had negative encounters in an artistic environment?

Vika: I am an anxious person, sensitive to unethical and unfriendly things. The most complicated thing is submitting applications or deciding to go somewhere: I will review all the calls a hundred times, and read everything about the institution in order to understand and evaluate how friendly it will be to me, whether I can get attacked there for being a feminist, for being a non-heterosexual woman, and, if I'm really lucky (but usually not lucky), whether I can speak from a non-binary position in this institution.

My "favorite" case is about one exhibition I did not take part in. We had a group chat of the exhibition, everyone was there: both the organizers and the artists. Every now and then there were all sorts of macho jokes in this chat, I was already on high alert, and after another one I wrote that this was a discriminatory joke, it had homophobic roots, and it was unpleasant for me, as a non-heterosexual woman. To which the organizers replied: "Well, okay, we were just joking, we'll also joke about feminists and vegans." I read it for a while and left the chat. I wrote to a co-organizer — I had previously talked to her about this situation — explaining that I, as a queer person, do not want to support an exhibition whose organizers allow such things to go on.

It is a huge intellectual and psychological work to spell it out, to provide informational service, to explain why this vocabulary is discriminatory, and why jokes are never just jokes, and why I may feel uncomfortable, but I have to do it.

We had a nice talk and parted on good terms, I thought that everything was over. But after some time, another organizer wrote to me and began to mansplain to me [mansplaining is a sexist manner used by men explaining to a woman what she already understands, questioning her expertise. — editor's note] and said that "actually, this exhibition can't be sexist, because it was prepared by a feminist."

When you are a woman, and when you are a queer woman, you encounter discrimination everywhere, and it is a terrible myth that things are bad only in state institutions. In the alternative and protest social circuits there are also a lot of sexists, people using homophobic rhetoric, not giving a platform for queer persons, feminist works, but it's often less noticeable. And when everyone in the chat justifies such behavior, I involuntarily begin to doubt myself: maybe I'm overreacting with my agenda, maybe my anxiety is the problem, and not our society and community. We live in a country where everything is devalued, where in order to survive you need to be able to keep quiet, and when you face such discriminatory things, in addition to feeling unsafe it also makes you doubt if you're right, if it's legitimate to object.

Yana: What 2020 was like for you? From the beginning to the end, what difficulties did you meet?

Vika: I will say a not very popular thing, maybe not even very ethical, but at the beginning of the pandemic, when the lockdown just begun, I felt good: I really liked self-isolation, I felt that I now had a legitimate reason not to go to university, and it was almost a political statement. I usually spend a lot of time at home, and for me this is a resourceful state. Here I must say that I have the privilege of being at home in a safe space with my loving, caring partner and having a great relationship with her. In my head, self-isolation felt like a separation from an unsafe reality, which has now become unsafe for everyone. So I felt good for some part of the quarantine. I didn't work, so I didn't suffer any financial loss, fortunately, none of my relatives got seriously ill. At the very beginning, I had thoughts as if I was inside a film, living in a historical era, and I even felt curious, I tried to look around to remember the peculiarities of our time. I didn't know then what era I would live in next.

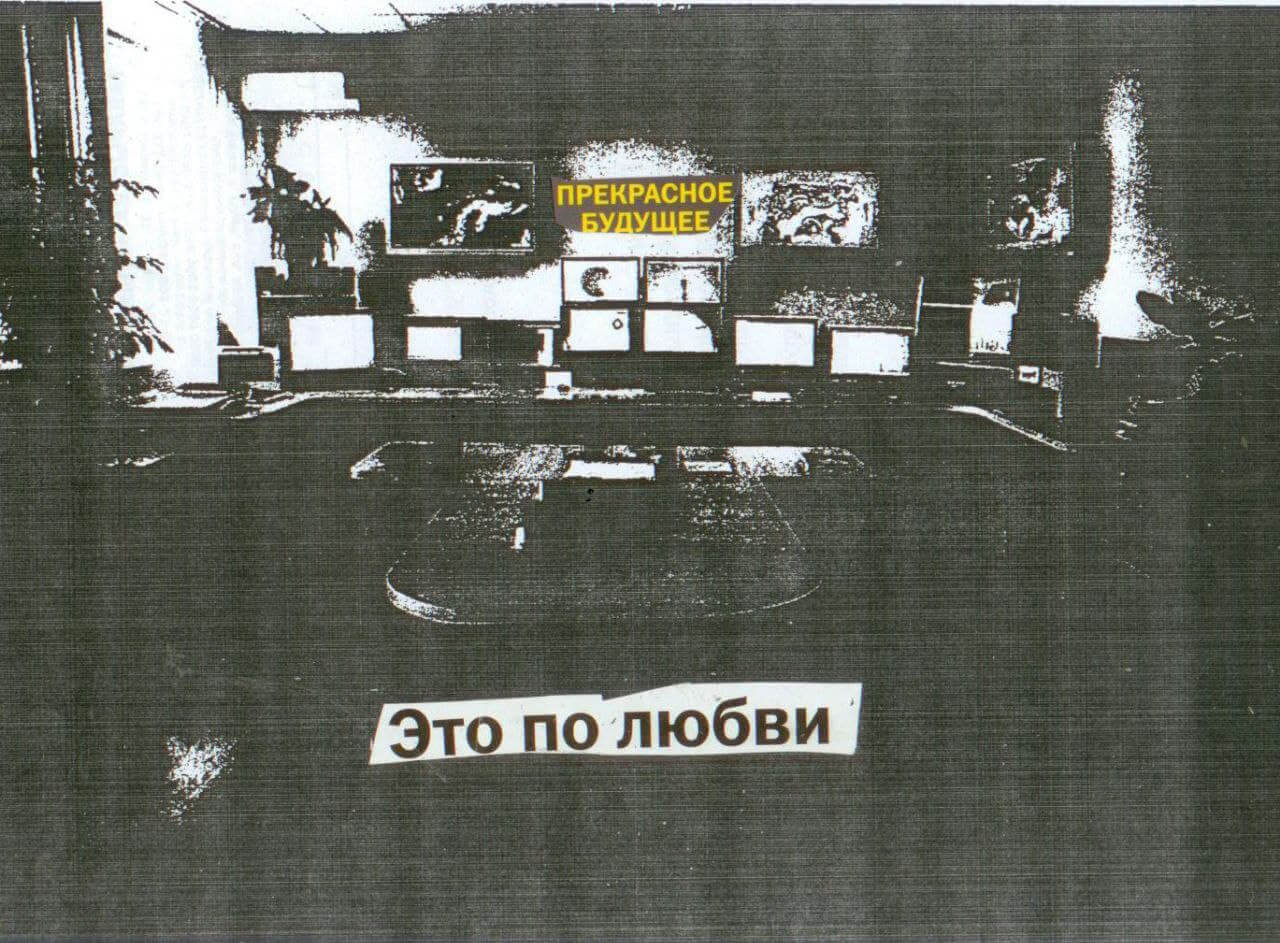

© Vika Grebennikova, "Heaven is where the police"

© Vika Grebennikova, "Heaven is where the police"Yana: How did the elections affect your life and art?

Vika: Tremendously. My low profile helps me, because if I were visible in the mass media, an artist with a larger audience, then I think I would have already been in jail or fled.

Alina and I had thoughts of moving to Kiev. You know, sometimes you watch historical films about genocide, and you want to shout at the screen so that they leave while they can, and she and I thought whether we would be the people who did not leave the country while it was possible. This panic, the feeling that it was necessary to leave while everything was still not too bad came occasionally, because it seemed that it could be even worse, infinitely worse.

I think that I am already a completely different person compared to the one I was before the election. I have a feeling that I was such a good little girl, kind and innocent. I began to feel less shame for myself, for my uncomfortable identities, which is good. I began to feel that I could talk more boldly about protests in my works. I cut out a heart from my passport for an installation and wondered if they could put me in jail for this. Is this considered a desecration of national symbols? Still, such thoughts come sometimes. But now I feel that this is an option I have. That I can work with these subjects. It helped a lot that there was a queer block during the protests in Minsk. This gave me the strength not to be afraid of "mixing the agendas".

Yana: What are you dreaming of?

Vika: I dream of not having to emigrate, of feeling comfortable, safe and cool in the country where I was born. I dream of having good gay-friendly mental healthcare that will be available for free throughout Belarus. I dream of living in a post-capitalist paradise, where I will not need to legitimize my art through money and people will not need to depend on how much they get and think about where they can earn more. Objectively, I do not believe that this will happen in my lifetime. I also think that it would be very cool for the labour of activists and artists to be paid now, while we haven't yet reached post-capitalism, and so that I would not be ashamed of the fact that I want this labour to be paid. In general, I wish this to all people, but I have a dream that I will be able to provide myself with a good, comfortable life through my activities. My dreams match the life that I have. I also have a dream to have money to go to a dentist and get all the fillings — that's the bloody kind of dreams Belarusian artists have.

Yana: Introduce yourself :) Tell us about yourself, about your identity, how do you want to be seen? Can you call yourself a queer artist? Do you consider yourself an activist?

Varya: My name is Varya, I am an artist, a clever, sensible woman, a worker, a simpleton. I would say that I'm still looking for myself, I'm making a fluffy yeast dough out of dry flour pieces. That's about how I want to be seen — exploring. It is also important for me to say that I consist of the concepts of "a small city" and "a poor family": I remember the names of almost all of my peers in my hometown. I used to think that this should not define me, and I tried to hide it and drown it out so as not to be perceived like that, I censored myself. Yes, I'm also a queer artist. I want to talk about it much louder and clearer. Now I define myself through all these concepts.

© Varya Sudnik

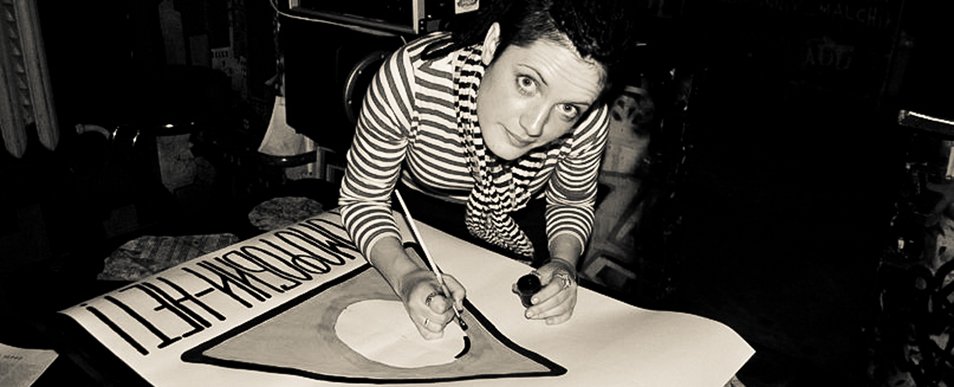

© Varya SudnikYana: Tell us about your creative history. When did you become interested in art and realize that you wanted to make it? Where did you start? Have you studied somewhere?

Varya: Initially, only other people defined me as an artist. I learned to paint still lifes and portraits in art schools and therefore I appeared as such to others. I rejected this word many times in order not to feel the need to be in art all the time: I did not earn money from my art and felt that this was an environment where I had no money to develop. Now I have appropriated this word again and use it according to my will and desire. New artistic practices have become the tool that is most native and close to me, I can express what is important and interesting for me, bring myself closer to the struggle that I need.

Yana: What forms and materials are closer to you? Which ones would you like to try to work with? What subjects do you work with most often?

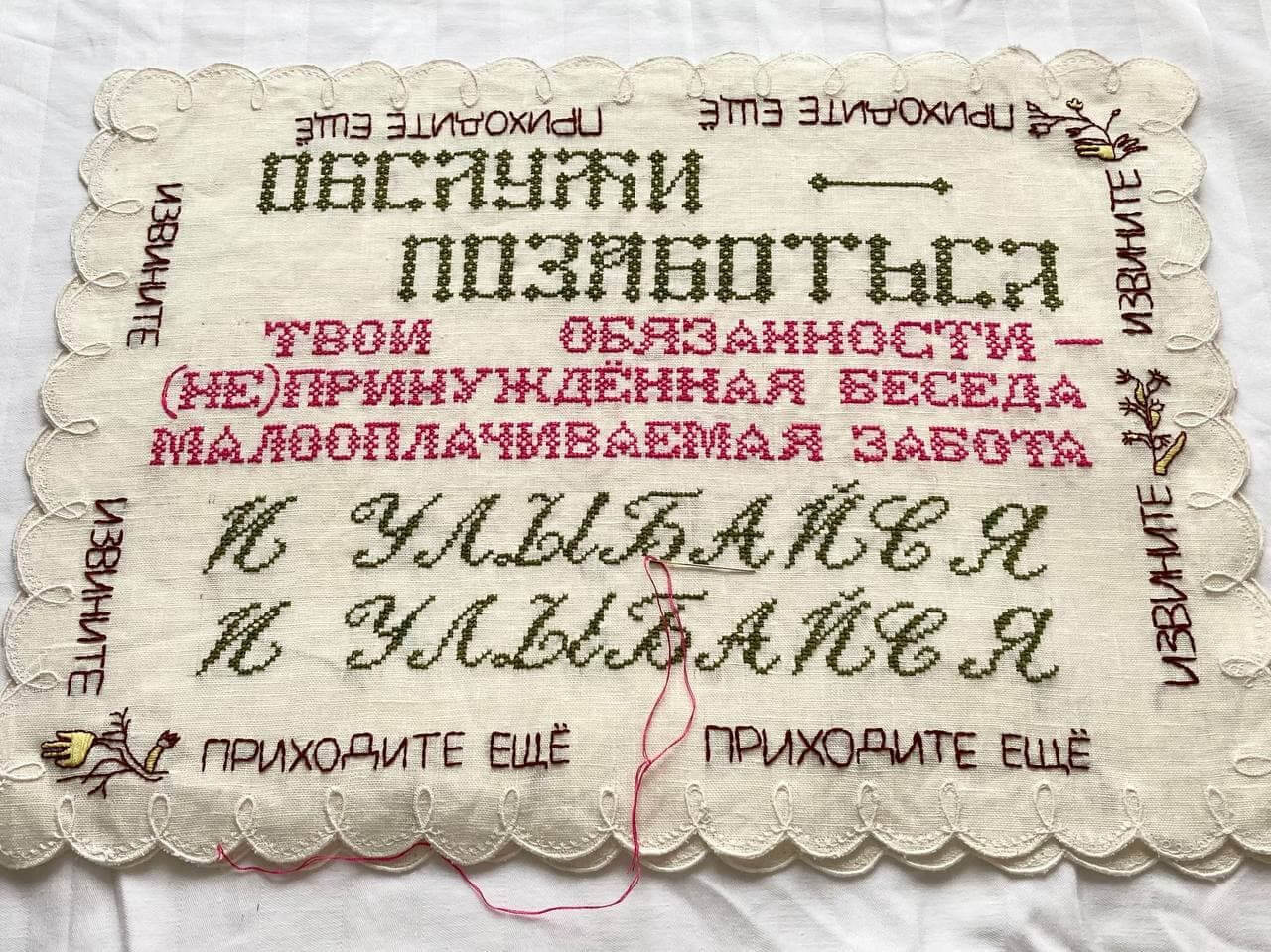

Varya: Now I am very interested in fabric: how it fits, crumples and crinkles, its soft tactility. I like embroidery for its long process that I can't speed up, and for the limits that I feel. The upside is, fabric is also an affordable material.

Three years ago, I made a video called "I Put Down the Shovel and Took a Closer Look", it was my first work in a non-academic genre. I watched the workers near my school and filmed them. It was about choosing a profession and devaluing low-paid workers, about respect. Now I do the same jobs myself and I still talk about human dignity and respect, but owing to my experience, I want to raise issues of pay and working conditions, exploitation. So one of the most important subjects for me now is labor rights. The latest related work is a piece of embroidery titled "Shifts 2/2". I suffered it with love in my heart. These napkins are my manifestation of both struggle and humility, acceptance.

I also really want to work with the mystery of old houses, forests, rooms, things, crosses at the entrances to villages. It takes my breath away. I make linocuts out of old windows, I like to combine them with aged lace found at home.

In the future, I want to talk about power and fear, schooldays, pride, fragility, vulnerability, small cities — now I study, collect and look for it inside myself.

© Varya Sudnik, from the series "Shifts 2/2"

© Varya Sudnik, from the series "Shifts 2/2"Yana: I follow you on Instagram and I see that you write a lot about exploitation, about your experience of living under it. Does verbalizing it help you? Where do you get the courage to talk about it?

Varya: I felt quite stupid and humiliated, trying to balance between creating projects on some other subjects and working for a penny in different places. Now I am regaining my pride, through artistic practices among other things. I have absorbed a lot of obedience, so first I take a hit, then I redirect it and rethink it, to be honest.

I am not only an artist, I do not have an opportunity to exist in some kind of artistic bohemian vacuum, so I want to talk about this again and again, I want everyone to be safe.

Speaking gives me a lot of strength and confidence, I don't feel as abandoned, I like to express my experience through words, it becomes stronger for me. This is my way.

In general, I want to tell you that even in the coolest places, for example, in Minsk, the conditions and wages at the lower levels are often terrible. Naturally, they make excuses saying they have great goals and a great service.

I would like everyone who goes to such places to drink a glass of wine, try modern cuisine, buy cool things to be aware of this. I'm already sick of such places, it's hard for me to go there, I perceive everything differently — it's very painful.

Yana: Have you faced stereotypes and discrimination in an artistic environment as a woman? As a queer person? Has it ever happened that your artistic work was devalued?

Varya: I get most depreciation from myself, this kind is more memorable.

Yana: What are you dreaming of?

Varya: It's hard to come up with dreams! I dream of a world where the unprotected feel protected, I dream of justice, I dream of finding answers to questions and then finding them again, I dream of having strength.

I dream of everyone having a place to live, so that everyone has the opportunity to relax, so that there is no imbalance. I dream of all the old shelf stands, sofas, tables, books in rented apartments finding their peace, their owners who will love them.

Yana: Which Belarusian queer artist (or other creative person) would you like to tell people about?

Varya: I am passionate about the researches, collages, and Instagram posts of Vika Grebennikova. I really like the ways Zlata Lebedz expresses herself, I like her photos and paintings. I am also very interested in watching what you are doing, Yana, for example, your embroidery. I feel solidarity with these artists.

Thanks!

Yana: Introduce yourself :) Tell us about yourself, about your identity, how do you want to be seen? Can you call yourself a queer artist? Do you consider yourself an activist?

yul: My name is yul, but in on-line spaces I use the name Astrantius Mon. I am an intersectional feminist and queer activist from Mogilev. Now I define myself as queer and genderqueer, I prefer the pronouns "she/they". I'm also a tired student, translator and artist.

Yana: Tell us about your creative history. When did you become interested in art and realize that you wanted to make it? Where did you start? Have you studied somewhere?

yul: I started drawing and doing creative work as a child — I think one can still see paint stains and traces of clay dough on the carpet of my old house. My interest in art was supported by my love of cartoons: before school, I often sat in front of the TV and redrew my favorite characters. I never went to art school, but I went to different hobby clubs where I experimented with my creativity.

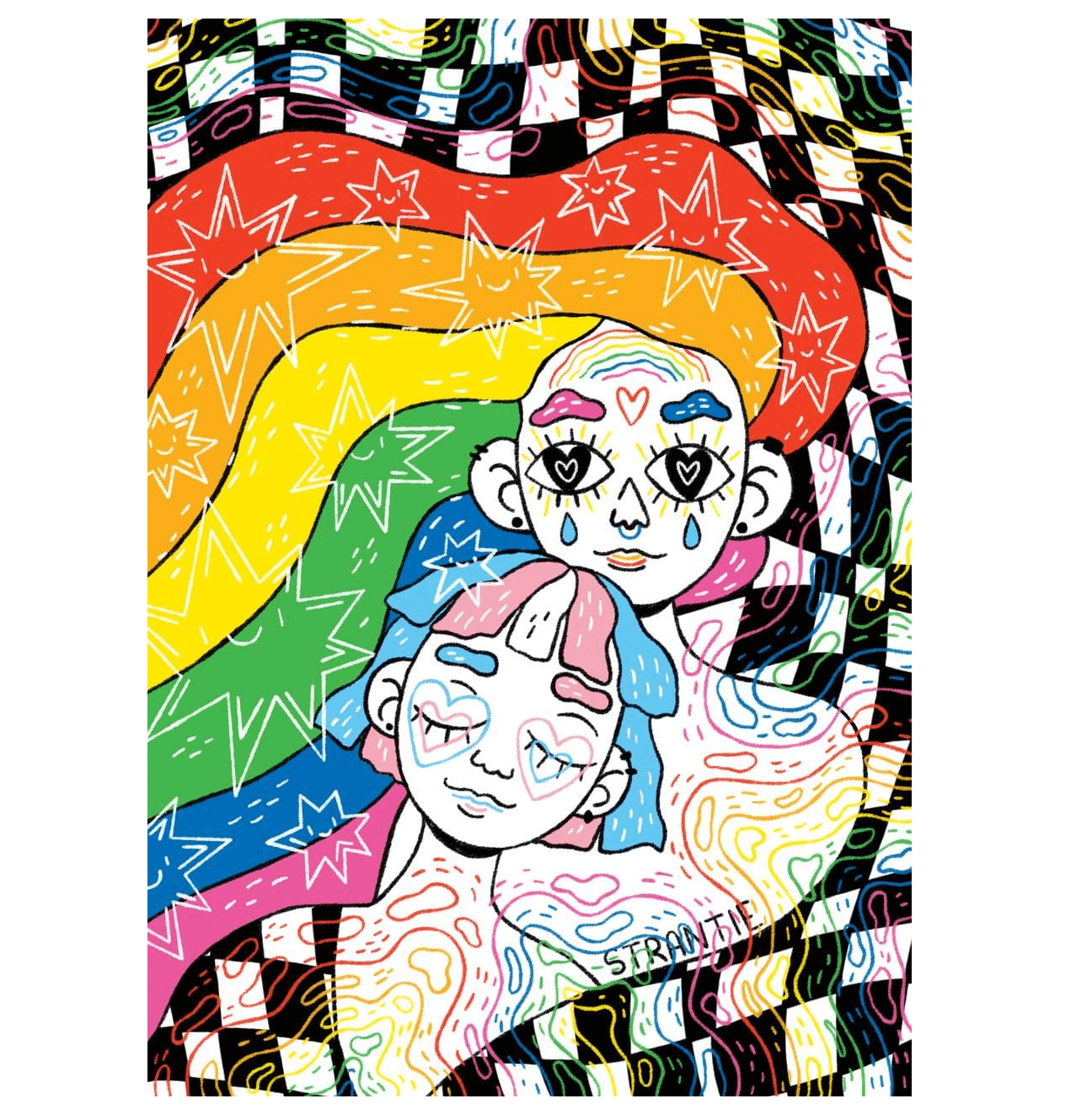

© Astrantius Mon

© Astrantius MonYana: What forms and materials are closer to you? Which ones would you like to try to work with? What subjects do you work with most often?

yul: Currently, I like to make collages from magazines most of all: you never know what you will find in them. I recently cut out an article about telegony and a test called "Is Your Partner Gay?" I am attracted to the comic book format in drawing, I even want to release my zine someday!

I think I don't have a specific subject yet, I just draw my life and friends. I am interested in art-activism, I want to go deeper into it in the future. Recently, I have been dreaming of making something three-dimensional, for example, a paper mache sculpture, or painting clothes.

Yana: Please tell us about your project "Nie Zdajetsa" ("It doesn't seem to you").

yul: "Nie Zdajetsa" is a small intersectional initiative in Mogilev which we organized with my colleague Daria Gromova. By the way, we recently held our first event about queer flags. For me, "Nie Zdajetsa" is a mixture of activism and creativity, and I liked both making collages for posts and conducting a workshop on rainbow felt pin badges :)

This year you did a project for May 17 [International Day against Homophobia, Biphobia and Transphobia — editor's note ] where you sent cool supportive postcards to queer people by mail. Can you tell us a little about it?

The postcard project was born at the OUTLOUD training course — together with our colleagues we decided to organize an action dedicated to the International Day against Homo -, Trans - and Biphobia. The design for the postcards was created by me and an illustrator Edward Walker; Daria Gromova and Maria Slabzhennikova worked with me on the project. With the help of this action we wanted to draw attention to discrimination, as well as to support the queer community. I think we have succeeded: we have sent more than one hundred and fifty postcards all over Belarus!

© Astrantius Mon

© Astrantius MonYana: Have you faced stereotypes and discrimination in an artistic environment as a woman? As a queer person? Has it ever happened that your artistic work was devalued?

yul: I had no experience of discrimination in the artistic environment, but I'm not surprised: my works rarely get into the feed of aggressive people. Even if I received some negative comments before, I deleted them and happily forgot about it. I consider myself the strictest critic, so sometimes I devalue my work myself. That's why I am very grateful to my friends for their support!

Yana: How did the pandemic and the revolution affect you? What helped you to cope with the difficult times and also to find the strength to create art? What has changed in your life in connection with these events?

yul: Sometimes I find myself thinking that everything that is happening is another series from Netflix. You know, like "Derry Girls": it seems as if it's just ordinary life, but in the background the history unfolds. To be honest, it's terribly tiresome, and I want everything to end as soon as possible.

I feel like I've lost a lot of resources over the past year. I still have ideas for drawings, but I don't have the same energy to implement them. Now I pay more attention to different types of needlework: embroidery, knitting and beading. It calms me down.

Yana: What are you dreaming of?

yul: I dream of freedom.

Yana: Which Belarusian queer artist (or other creative person) would you like to tell people about?

yul: I want to share the work of an amazing artist, Ami.