and I will tell you about it, whether you want it or not

A warning for those who are preparing to say "Stop speaking for all trans people in Belarus", or "For all trans guys", or "For all people with a mastectomy": no one's personal experience can erase the experience of a huge number of people. If at least one person besides me goes through a similar thing, then the text is not written in vain.

A warning for those who expect an unambiguous message like "Remove your breast, it's fun" or "This body mutilation is a conspiracy of the trans lobby": only you know what you need and what you don't need to do with your body.

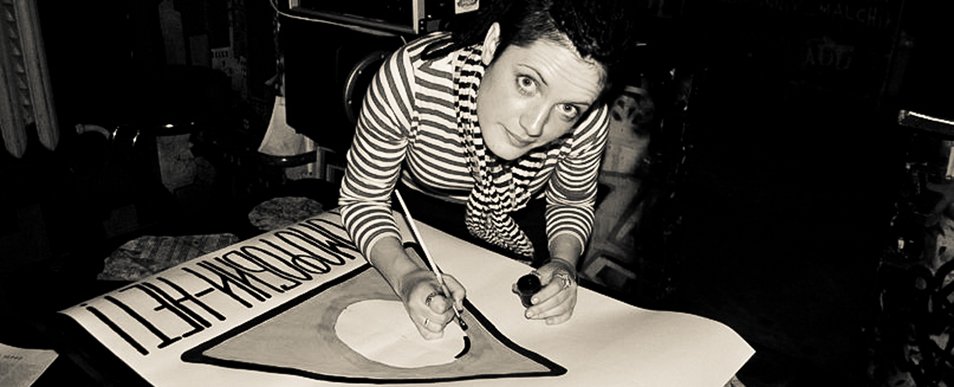

That's why I write this text myself and don't give interviews: no matter how sensitive some media outlet is, conversations about a transition too often slip into "Look, someone cut off / attached to themself some body part!" We look at the situation through the eyes of a non-queer person. Someone who does not imagine (or does not want to imagine) how much mind and body can be torn apart from each other — by personal trauma or the daily need to be among people who expect something from you. I have explained many times to journalists why they must not write "a girl has become a boy": because magic "cutting off" or "attaching" some organs does not turn one person into another. I am the same person before and after the mastectomy. Both now and then I deserve acceptance.

Also, I want to focus on the Belarusian context: I am telling this story as a person who couldn't afford a paid surgery and / or have it done in another country and who experienced the state procedure of free surgical transition in Belarus.

My background

I am twenty-four years old, and I am sick and tired of looking for a name for my identity. I fluctuated in the LGBT + spectrum from a bi-girl who is "a bit tomboyish" to an FTM-transgender person who wants a patriarchal family with a million children. None of those options was one hundred percent suitable. There should be a paragraph here about how I have discovered my true self, but I haven't — there will be no revelation, we're done.

The only label that doesn't make me sick is "queer". I am a queer person, and it describes my sexual and gender identity, my appearance, and my not giving a damn about all of it.

But in Belarus, you can legally be either a woman or a man — and I chose the latter. This option allows me to be named Evgeny officially (and this is the best name on the planet, I'm sure), marry those who have an “F” gender marker in their passport, and masculinize my body. It is bundled with congratulations on Defender of the Fatherland Day and the expectation that you will always help to move a wardrobe, but everything has its drawbacks. In order for the Belarusian healthcare system to allow me to be Evgeny in spite of me having a vagina, I had to prove that I was a real man. Although I am definitely more of a man than a woman, it turned out to be difficult: post-Soviet sexology believes that I should love sports, short haircuts, women and fucking (women). But I'm a long-haired queer musician, well, what can you do?

However, within a few years, I was at the first medical panel that defined my dysphoria as "denial of one's biological sex syndrome" (but the only kind of sex I deny is them fucking my brain with their gender stereotypes), changed my ID, spent a year collecting papers for the second panel, attended it, and then lived through two waves of COVID and before the third one hit got a mastectomy, or rather, masculinizing breast surgery where my breast was removed and the chest modified to look more masculine.

© Nollaig Lou

© Nollaig LouBefore the surgery

Queer people are not created for clinics. It's not just about gynecology and andrology: in a state medical institution, literally any disease can be associated with your "immoral lifestyle", whether it's an unusual appearance (by nature or after modifications), non-heterosexuality or asexuality — yes, anything that the doctor might not like. Once my acute cystitis was explained by a new tattoo. Don't ask me.

Being trans is a universal tool to break the mold of Belarusian medical workers. "But you're openly laughing at this, you get off on attracting attention," you might say, and you will be right only in the first part: I really laugh, because if you take this seriously, you can go crazy. I've never wanted to attract attention like this. Not in a doctor's office. Not when I'm ill. Not when my body completely belongs to a system that does not consider me a person. There are more pleasant ways to show off. And when I'm ill it's just like with any other people — and I expect the same attitude to me.

"Evgeny Dmitrievich? Why is there a gynecologist's examination in your medical record? Is this an examination of your wife? Is this your husband's card?" — a thousand and one question from medical workers, whose life will never be the same after meeting me. I look androgynous, my voice has a wide range, and I'm okay with that; unfortunately, in this country, a doctor can't treat my cold without asking if I'm going to have a phalloplasty. And no, we are not talking about medical issues like hormones, removed or implanted organs, etc. I'm talking about a receptionist yelling so loud that the whole clinic hears: "Luda, come here, look, someone's changing sex here! Imagine, this happens in Belarus!", and at an appointment with an infectologist, I hear "Oh, it's a pity, you would be such a beautiful girl", to which I always have one answer: first, all girls are beautiful, and secondly, I'm fucking hot in any gender.

Private clinics are better sometimes, and sometimes they are not different in any way. Everything is clear here: the more money and respect the doctor receives, the stronger their motivation to treat clients like a human being is (this is generally the case in any profession). But if you are an indifferent person, then no social benefits will make you a more decent doctor.

I will not give a list of examinations that a trans person needs to undergo before a mastectomy: it has changed over the years and differs in various clinics. Basically, they include ultrasound scans, blood and immune tests and therapeutic examinations — the referral is issued by the doctor of the clinic where you plan to get the surgery.

© Nollaig Lou

© Nollaig LouFrom the beginning and until the very discharge from the hospital, I got the message of the system: "If you need it, do it yourself." The fact that there has been no district therapist in the clinic for five years, that you can get an appointment only a month prior, that 90% of tests need to be taken in other clinics, for a fee and with huge waiting time that does not fit into the pre-surgery schedule, is, they say, only your problem. No one cares where you go and how much you pay. You don't have a single physical disease, which means that you are healthy, and any medical intervention is your personal whim. Be grateful that the state allows you to do this nonsense.

I will not start a discussion about the importance of surgical transition — there is a World Health Organization for this. I will only say that a cis woman who decided to increase her breast will get more respect from medical workers than a trans woman during her transition, although the surgeries are the same — hello, double standards.

I mean, I don't need special treatment. I need to be treated the same as everyone else. No doctor will ever ask a cis guy who comes to an appointment if he wants to be a girl — and I don't want to hear this question as well.

There may be another batch of comments with the classic victim blaming: someone might say that in order for me to be treated normally, I need to stop showing off and look like a normal guy. And here I don't even have any arguments. Well, yes, in order not to be bullied, you need to be like everyone. Nothing new.

Only you can't imagine how happy you can be when you allow yourself to be yourself.

In the hospital

In continuation of the topic "It's only you who need it": if you have questions about your health, then most likely the Internet will tell you more than your attending doctors, but it is important to know where to look. Forums and your trans friends will not help to make completely correct predictions: the results of a surgical transition (as well as hormonal) are very individual. I found the materials collected by trans activist organizations very helpful. For example, the publications of the "T-Action" initiative are a cool source of information in Russian. Personally, the book "Trans-health: Physical health of transgender people" explained a lot to me. Here you can read about the types of surgeries, the recovery period, approximate results, risks, etc.

How can I say that the Internet is better than competent specialists? The thing is, I did not say this: firstly, there are many materials on the Internet from those most competent specialists, and secondly, if you find doctors in your area who will give you the most complete and truthful information, then I am sincerely happy for you. And in my experience, it is good if out of ten doctors in Minsk, at least one spoke to me without ridicule, rudeness and humiliation.

Is it possible to get a mastectomy without hormone therapy? "And why do you need it? Why aren't you taking hormones? Do you doubt that you are a boy? People like you detransition and drag us before the courts!"

How long will the swelling last? "How do I know? You asked for this surgery yourself, so you will wait as long as necessary."

How old can my ultrasound scans be? "Listen, don't you think you're making too much drama?"

These are real conversations with real doctors.

There is no official sex education in Belarus and, accordingly, there are no official sources of information about trans health. You can only hope that the doctor will like you, and for this you need to be enough of a man or enough of a woman — noone knows about non-binary transition here. As practice shows, the queerer you are, the less likely you are to be liked at least by someone in this country.

© Nollaig Lou

© Nollaig LouDuring the surgery

I will say right away: I am grateful to the doctors who operated on me at high quality standards and without complications. I believe that they should receive much, much more from the state for such work — both money and respect for the profession. I think that such surgeries are a real miracle.

But I think I got another PTSD that day.

I have had severe chronic depression and generalized anxiety disorder for many years. This is the first surgery I got as an adult: when I lie down on the operating table, I breathe heavily and seem to whine with horror — I am afraid that I am about to die.

"What an ugly thing, — someone says at the table, pointing at the tattoos on my arms. — Have you been in jail?"

My approaching panic attack was stopped by my own laughter. I'm lying here, preparing to die, and the doctor scolds me for my tattoos. It seemed funny at the time.

"I'm asking you, have you been in jail?" — I mean, this is not a rhetorical question, the person really wants to hear the answer, since he literally yells in my ear.

I think that if I tell him to get off of me, he may harm me during the surgery. Now, after a while, this idea seems very familiar to me. Don't upset your drunk uncle, or he'll beat you up. Don't argue with your boss, or he'll fire you. Do not oppose the state, or you will live even worse than now.

"Thanks for cheering me up" — being sarcastic when it seems that you are dying is priceless.

I would like to add: yes, I was in jail. In the Zhodino prison. For the happy future of my country. But this information can only make things worse.

"No one will cheer you up here. You don't have appendicitis, you're not dying. You wanted this surgery yourself, so lie down and bear it. No one here sympathizes with you."

As in any similar situation, I manage to dissociate: maybe this body is defenseless, maybe it is vulnerable and will suffer now, but I am outside of it, I am here, I am complete, I cannot be destroyed.

(If you wanted to hear the answer to the question from the beginning of the text — why do trans / queer people have such a bad connection with their body — then here it is.)

That's why I need my publicity. Why I need my activism. That's why I turn my experience into a community memory. That scared child on the operating table needed an adult who would say: you're all right. Even when you are exposed and vulnerable, you are stronger than all of them. They wouldn't be able to do it if they were you.

© Nollaig Lou

© Nollaig LouAnd now I am telling this child with this text: it doesn't matter that none of them loves you, know that I love you.

Before I was completely anesthetized, another doctor spoke to me. He was young, probably also scared; he said: "Why are you shaking? Don't be afraid, there's nothing to be afraid of, everything will be fine." His South Asian appearance and strong accent had obviously been a target of numerous occasions of xenophobia, so this awkward concern of his turned out to be so important to me that I regret that I did not have time to thank him.

A small greeting from one vulnerable group to another.

After the surgery

Since you are reading this text, it means that I am alive, relatively healthy and have not lost the desire to describe all this. The postoperative period was difficult, but tolerable: each day it was becoming easier for me to move. My collection of button shirts came in very handy, because it is impossible to put on a T-shirt without raising your hands, and oversized clothes do not pull the bandage and drains. It was hard not to move, so I remind neurotic people like me: excessive activity will not speed up recovery (and maybe even slow it down), everyone should take their time and move at their own pace. Move smoothly, do not hurt yourself and take painkillers. If there are no complications (and it's hard not to notice them; if you doubt it — go to the doctor), then everything will heal in the end, you just need to be patient.

A week after the surgery, the drains were removed and I was discharged home. In two weeks, I washed on my own. In three weeks, I moved at my usual pace and even did some things. In a month, I was allowed to remove the bandage.

Two months later, I'm walking around the city in a thin light T-shirt and I don't want to sink into the floor because of dysphoria. I take dramatic selfies in the mirror with a naked torso, in test mode for now: the scars are still bright (because of the large size of my breast, I have had a double incision surgery), but they should lighten up within a year, besides, I plan to cover them with tattoos. I enjoy the privilege of not dying from extra layers of clothing and the body parts falling off while running (one day we will live in a wonderful post-gender world, where gender-affirming surgeries are available not only to trans people, but in general to everyone who wants them, but this is a completely different story). I swim in a pond just in swimming trunks: to be honest, when I undressed in front of strangers for the first time, then entered the water and swam — I almost burst into tears with happiness. Then I realized: I recovered, everything is over.

The surgery was performed by doctors, but I also did something important — I dared and made an effort.

Unfortunately, part of the chest has lost sensitivity: perhaps because of the large incision area, perhaps because of my activity after the surgery, perhaps the body just decided so. Nerve endings either recover within a couple of years, or do not recover at all. For many, this can be a serious loss, for example, if it is an erogenous zone. But, since my breast was not particularly sensitive before the surgery, I lost absolutely nothing in terms of sex. I still have a slight feeling of tightness when I raise my arms, but this will also pass within a couple of months.

The most difficult stage was postoperative depression (in my case — aggravated by a permanent one). Dysphoria does not go away at the snap of a finger: even after the surgery, there were thoughts that I had too feminine curves, that my breast was still visible, that I needed to look even more masculine. But I know that my dysphoria turns on for a certain period, and then it lets go. For others, it may work differently — and this is OK. As I have already said, cutting off or attaching anything to us does not change our personality: neuroses, anxiety, self-hatred remain with us. But we are able to do at least what depends on us: care about our mental health and / or change our body the way we want.

Healing is not quick, especially when it comes to our psyche.

Apart from the hypochondriac "I have cramps, probably I'm dying", during these two months I have never regretted the surgery. My life has become much easier, and my dysphoria is much weaker. But if in a month, a year or ten years I say "damn, I want my breast back", then this is not a reason to devalue my current experience.

Detransition is not shameful, coming out with a new identity is not shameful, changing yourself and your body in any direction is not shameful. We are not static, our ideas about ourselves are transforming, and this is absolutely normal.

I am not writing this text in order to persuade someone to take some actions. One cannot propagandize transition, as well as homosexuality. Until there is as much information about transition as about the bodies and minds of cis people, there can be no equality or, gods forbid, discrimination against these very cis people. I spread information: I tell funny stories about my life, I support them with all sorts of scientific data, and you draw conclusions. And you choose which ones.

But no matter what you decide, I remind you: your body is your business.

And my body, by the way, is gorgeous.