Alice, a coordinator of a trans activist initiative TG House, told us about the lives of transgender people in Belarus a year after the beginning of the pandemic and the socio-political crisis.

Milana: Let's remember last year's campaign with food parcels for transgender people in a difficult life situation. In my experience, this was one of the first campaigns dedicated to targeted assistance for the trans community. Usually, when it comes to supporting vulnerable groups, we are talking about services like mental healthcare or free legal assistance in protecting one's rights, for example, in a case of labor discrimination. The very concept of targeted assistance is often criticized as "less effective". But the truth is that a huge number of people simply cannot use those services, because their problems are a step earlier, at the level of basic needs, when people simply have nothing to eat — because they have no home and work. And I think it's very cool that the campaign has been implemented. How do you rate it? How useful do you think it was after some time has passed? What was the primary result of the campaign: improving the financial situation of those people or providing emotional support?

Alice, TG House: Now I see that the effect was very significant. At least because of the fact that people might have seen for the first time that someone cared about them and paid attention to the needs of transgender people. That they are not left alone with their problems. I immediately remember how some people reacted to receiving help: when a person opens the door, sees a package of products, they are shocked — these first minutes tell me a lot about the psychological state and mood that existed in the community. People lived with the confidence, with the knowledge that no one has ever helped them and no one will. Our activists, who delivered aid, said that sometimes the doors were opened by the parents of a person who left the application. And when they found out that it was help from the Trans* Coalition [Trans* Coalition in the post-Soviet space is an organization dealing with discrimination against transgender, non-binary, queer persons, — editor's note], that people help each other so much in the community, I repeat, they were just shocked: no way anyone really cares about their families in a good way! We were later told that for some this was the starting point of a transformation in their child-parent relationship, that parents began to change their minds: the negative stereotypes that existed in their heads began to gradually collapse. Of course, this did not change people's whole lives, did not heal all the wounds — but this surprise prompted them to think.

© Mila Vedrova

© Mila Vedrova I think the most important thing was this attention, the recognition that you are important, that someone writes to you, thinks about your trouble. After all, it was not so easy — people did not leave applications on the website themselves. We had to use a lot of personal connections: to transmit information through our own channels, to offer, to persuade. Many simply did not believe that there was no catch there, that you could rely on gratuitous help, because you were in a difficult situation, they were expecting that something would be taken from them, that they would be deceived somewhere, or they said "give it to those who need it more" being in very austere conditions themselves. But thanks to word of mouth, we were able to help more than thirty people. Of course, as an activist, I understand perfectly well that those are not everyone who needed help, but for such a campaign this is a really good result.

Usually, in the conditions of targeted assistance, it is indicated that they are one-time programs. But sometimes there were really very difficult situations when a person found themself in a completely hopeless situation. Then we decided to make an exception and accepted a second application.

M.: Do you still keep in touch with the Trans* Coalition?

A.: Sure. We constantly keep in touch: Kazakhstan, Ukraine, Belarus, other countries of the post-Soviet space. We are also in touch with Transgender Europe, the largest European organization for the protection of trans rights.

We pass information to each other: if some applications come from Belarus, I see them all, everything is the same. We constantly accept applications for legal assistance, free medical and psychological consultations.

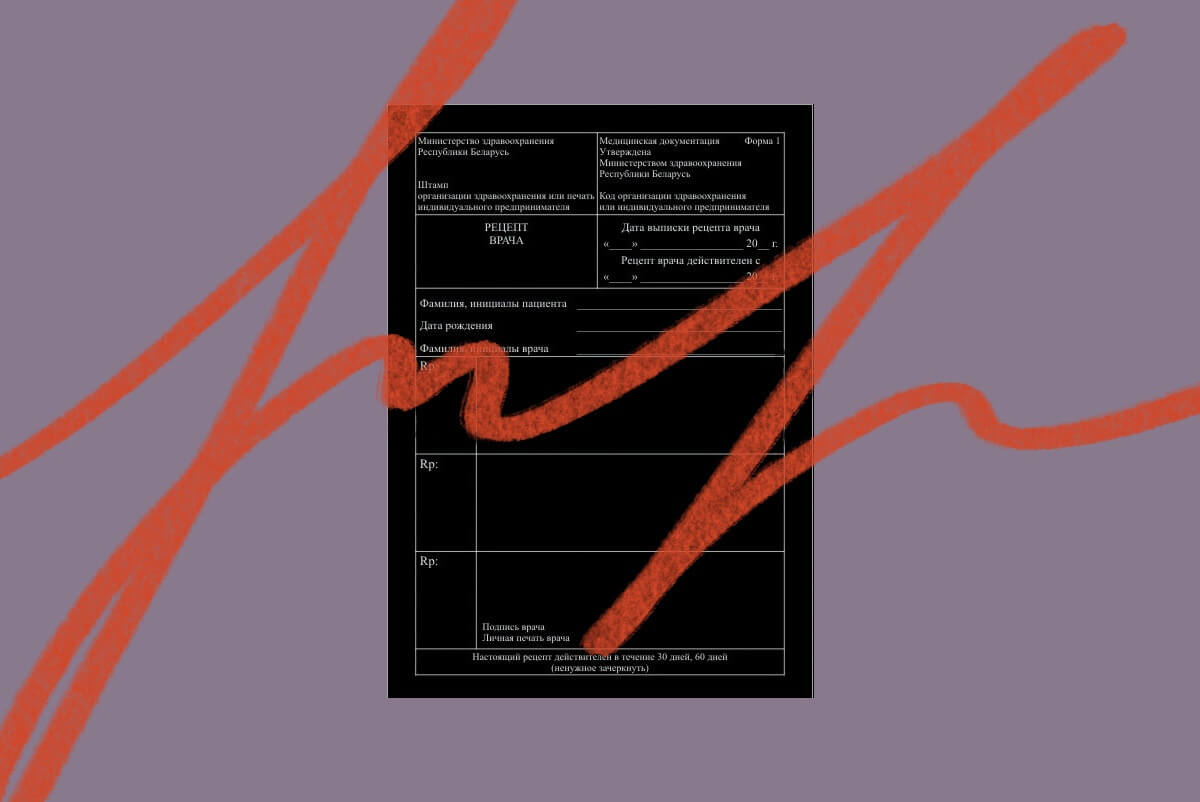

M.: Was there a medical panel organized during the pandemic [a meeting of doctors and other specialists who sanction first legal, then medical transition in Belarus, — editor's note]?

A.: Yes, there were two panels: in summer and in winter. I keep in touch with the people who have passed through those panels. There were twenty-seven people on the winter panel — everything is going according to plan here. Although, of course, such a number of people surprised me — there always used to be ten or fifteen people.

M.: Do you think this has happened because people are less afraid to interact with the official health care system and talk about themselves?

A.: This is also possible. Although, to be honest, I think it's just a coincidence: people could have submitted documents two years ago, now their time has come, and everyone was sent to one panel. Someone had their first panel, someone had their second, and they gather everyone. We can attribute this to the fact that people became less afraid, but just last week a girl came to us for advice, she was submitting documents — of course, she was trembling and scared. I tried to support her, to tell her how the whole mechanism of the panel work. I said: don't tremble, just come and tell everything about yourself as it is. But, of course, people are still worried.

© Mila Vedrova

© Mila Vedrova Last year, activists had a lot of ideas about some changes: there were talks about updating the system, brining new, more civilized legislative norms, but the political and social crisis of the past year froze them. Many activists burned out and suffered. It has become much more difficult at all levels: from working with authorities to communicating with the international community. For example, I know that this year, for a long time Transgender Europe could not get an answer from Belarus about the situation of the transgender community during the pandemic — simply because submitting reports and describing the progress also takes some internal efforts. And where can one get them if in the same month human rights defenders first meet with passport office employees on simplifying the legal transition, and then they are sentences to a few weeks in jail? Everything that is happening very much affects both one's performance and sense of security. Moreover, now prison conditions are much more severe. I had such an experience: a few years ago, I myself was detained for one day. But I see the testimonies of the past year and I understand that now they are simply incomparable. And this bleach, and mattresses… These things get stuck in your head, they affect lives — this is far from being about politics. You see, even we are just talking — and we still arrive to this subject. It's very hard to watch.

In the current situation, it is still very important to monitor our issues. It is clear that interacting with the system and lobbying are not worth it at the moment. The tools of legal protection are very limited — but it is still important to conduct at least some monitoring in order to understand what is happening to people, what problems they face.

M.: How much do you think this crisis has affected the trans community? The sense of security, a sense of one's prospects in this country? In Belarus today, for much more privileged groups, everything that is happening has become a reason for migration, but most transgender people simply do not have such an opportunity, they do not have a choice to "leave or stay", because the very opportunity to leave is often a privilege. Especially if we recall the pandemic, when even without problems with one's ID and financial cushion, movements are limited. At the same time, the idea to "leave this place" is very often perceived in the LGBT+ community in the CIS countries as some kind of life-saving dream. Has this idea transformed into something else? What do they say in the community when our agenda has completely left the focus of public attention?

A.: Of course, the problems of the trans community have not gone away. It seems to me that people just froze their expectations a little, recognizing the current situation. Many people are trying to get used to the current realities, although it is clear that all this accumulates inside — many do not cope themselves, they seek help from psychologists. Several of my friends from the trans community left — they had such an opportunity: someone for work, someone for humanitarian reasons. But most people stay and live here. It is very difficult to find work now. I will not say that everything is worse than it was — just because it has been bad already. But people began to talk less about it. Even when you write to someone "you had some problems, how are you now?", especially to people who, for example, wrote for the third time about targeted help, because the situation was just terrible — and they seemed to accept it, although it is impossible to accept it. We just accepted that we need to survive in the current moment. Because it is very difficult to leave. This is not only because of a visa and legal issues, but also because of a huge difficulty with socialization. Learning a language, finding a job, paying rent — when people face difficulties in these matters all their lives in their own country, they turn into an unrealistic task in a foreign one. And it is very important for me to remind that there is a global trans community.

If you have made this difficult decision to emigrate, please remember that you will not have to navigate it alone. In neighboring countries — in Poland, Lithuania — there are trans-activist organizations, like Transfusion, which can take care of some legal issues.

© Mila Vedrova

© Mila Vedrova M.: What supports you in these difficult days?

A.: My psychologist, who works with me and with our clients. But seriously, of course, my hope supports me: I believe that progress in human rights is inevitable, that evolution is inevitable. Everyone has phases of despair — I also sometimes just give up. But then I look at these huge prison sentences and I understand: it is impossible that they will be served to the end. For me, these enormous sentences is the limit of my understanding, and I firmly believe that this should not be and will not be this way. I have been involved in public and political life for many years, since 2008, and I know that there was no such solidarity and awareness before. Yes, we see everyday life around us now: people somehow live, go to work, but now they are more aware that it should not be like this.

M.: My last question is a practical one. When we talked about closed borders a year ago, there was a very difficult situation with hormone replacement therapy in Belarus: due to harsh restrictions, people could not buy it in the country or abroad. And how does it work these days?

A.: The restrictions were much tougher then — now everything is back to normal, you can order something from abroad. Now basically all medication is transported from Russia. The spring was the toughest, many countries tightly closed their borders then, nothing could be brought from there — now it has become simpler. Even the number of requests for consultations on HRT has decreased. In the spring, people constantly wrote to us, asking how to get therapy. It's not like that anymore. By the way, closed borders affected the activity of people: many began to look for information on how to help themselves, how to solve their problems, learned more about international organizations for transgender people — this is a big plus.

We at TG House also plan to develop international communication: now I am writing a monitoring report for Transgender Europe. It is important to look at how the community lives in dynamics, how the legislation works. For example, we have no changes in the laws that would improve the lives of transgender people. On the one hand, this is a bad indicator. On the other hand, sometimes rigid legislation also restrains negative changes: for example, 52 thousand signatures against the visibility of LGBT+ people in the media also did not bring results. It turns out that the legislation cannot be changed either for the better or for the worse:

We at TG House also plan to develop international communication: now I am writing a monitoring report for Transgender Europe. It is important to look at how the community lives in dynamics, how the legislation works. For example, we have no changes in the laws that would improve the lives of transgender people. On the one hand, this is a bad indicator. On the other hand, sometimes rigid legislation also restrains negative changes: for example, 52 thousand signatures against the visibility of LGBT+ people in the media also did not bring results. It turns out that the legislation cannot be changed either for the better or for the worse: